Minnesota’s Workforce Since the Pandemic: More Diverse, More Female, More Self-Employed

By Anthony Schaffhauser

December 2025

Key Takeaways

- All job growth came from workers of color. Minnesota added 20,246 jobs since the pandemic, but jobs held by white alone, non-Hispanic workers declined by 73,629 while BIPOC workers gained 93,874 jobs (+16.9%).

- Demographics drove the transformation. The white age 16 to 64 population declined 4.3% while the BIPOC working-age population grew 15%.

- Women now outpace men in employment. Female employment rates exceed male rates by 2.1 percentage points in 2024, up from 1.6 points in 2019.

- Prime-age men (25-44) are disconnecting from employment. Male employment rates in these prime working years declined, while women 35-44 held steady and women 45-54 had the highest employment rate of any group (87.5%).

- Teenager and senior employment is surging. Employment for ages 14-18 and 65+ grew at double-digit rates, reflecting both labor demand and delayed or interrupted retirements.

- Self-employment exploded among young adults. Self-employed workers age 19-24 more than doubled, only partially offsetting steep declines in wage and salary employment rates.

Introduction

Minnesota added 20,246 jobs from 2020 to 2025, climbing 0.7% above pre-pandemic levels. But this aggregate number conceals a dramatic reshaping of who works in Minnesota and how they work.

The pandemic marked a demographic tipping point in Minnesota. Workers of color now drive employment growth as the white workforce ages. Women have surpassed men in employment rates. Teenagers flooded into entry-level positions while seniors delayed or undid their retirement. And young adults increasingly have turned to self-employment.

These aren't temporary pandemic disruptions; they're accelerations of long-term demographic trends colliding with a pandemic-transformed labor market. Understanding these shifts is essential for employers struggling to fill positions, policymakers designing workforce programs, and anyone trying to navigate Minnesota's evolving economy.

Workers of Color Drive All Employment Growth

Minnesota added 20,246 jobs since the pandemic, but white alone, non-Hispanic workers – the state's largest workforce cohort – declined by 73,629 jobs. This means that all job gains came from workers of color.

The Census Bureau's Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI), which tracks wage and salary employment by demographic characteristics, reveal the scale of this shift. We average beginning-of-quarter employment for second through first quarter of the following year to reveal the trend from right before the pandemic – year to first quarter 2020 – to the most recent available data for year to first quarter 2025 (Table 1). QWI data are compiled as year to first quarter throughout this article.

| Table 1: Minnesota Employment Change by Race and Ethnicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or Ethnic Group | Number of Jobs,

Year to First Quarter* |

Change 2015 to 2020 | Change 2020 to 2025 | ||||

| 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| White Alone | 2,279,111 | 2,335,054 | 2,261,426 | 55,944 | 2.5% | -73,629 | -3.2% |

| Black or African American Alone | 141,901 | 187,340 | 213,888 | 45,439 | 32.0% | 26,548 | 14.2% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native Alone | 18,802 | 21,108 | 21,749 | 2,306 | 12.3% | 641 | 3.0% |

| Asian Alone | 119,784 | 153,660 | 169,985 | 33,876 | 28.3% | 16,325 | 10.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Alone | 1,757 | 2,550 | 3,206 | 793 | 45.1% | 656 | 25.7% |

| Two or More Race Groups | 35,741 | 47,614 | 57,000 | 11,873 | 33.2% | 9,386 | 19.7% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 108,999 | 144,718 | 185,037 | 35,719 | 32.8% | 40,319 | 27.9% |

| Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) | 426,985 | 556,990 | 650,864 | 130,005 | 30.4% | 93,874 | 16.9% |

| Total, All Races, All Ethnicities | 2,706,095 | 2,892,044 | 2,912,289 | 185,949 | 6.9% | 20,246 | 0.7% |

|

* To control for seasonal fluctuations while using the most recent data, we compare average annual employment for four quarters from the beginning of second quarter through the beginning of first quarter, or "year to first quarter." Source: Quarterly Workforce Indicators |

|||||||

Employment grew for every Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) group from 2020 to 2025:

- Hispanic or Latino workers: +40,319 jobs (+27.9%)

- Black or African American Alone: +26,548 (+14.2%)

- Asian Alone: +16,325 (+10.6%)

- Two or More Race Groups: +9,386 (+19.7%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native Alone: +641 (+3.0%)

The Pandemic Marked a Tipping Point, but Demographics Drove the Change

This diversity trend isn't new; it has been documented back to 1995. In the five years before the pandemic, every BIPOC group grew faster than white alone workers. What changed post-pandemic is that white, non-Hispanic employment didn't just grow slower, it declined.

The difference from the five years prior to the pandemic is that labor force growth slowed. Minnesota's labor force grew by 3.5% (106,241workers) from 2015 to 2019, but grew by only 0.4% (13,047 workers) from 2020 to 2024. Pandemic impacts pulled labor force participation well below trend in 2021, removing tens of thousands of workers. However, slower population growth and the aging population have caused the slowed labor force growth since.

The underlying cause is demographic. Minnesota's traditional working-age population (16-64) declined slightly from 2020 to 2024, but only the white, non-Hispanic cohort shrank (Table 2).

| Table 2: Minnesota Age 16 to 64 Population Change by Race and Ethnicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or Ethnic Group | April 2020 | July 2024 | Change 2020 to 2024 | |

| Number | Percent | |||

| White Alone | 2,822,324 | 2,701,624 | -120,700 | -4.3% |

| Black or African American Alone | 251,383 | 295,093 | 43,710 | 17.4% |

| Asian Alone | 202,701 | 224,792 | 22,091 | 10.9% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native Alone | 37,643 | 38,002 | 359 | 1.0% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Alone | 1,988 | 2,409 | 421 | 21.2% |

| Two or More Race Groups | 68,601 | 81,565 | 12,964 | 18.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 216,273 | 253,833 | 37,560 | 17.4% |

| Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) | 778,589 | 895,694 | 117,105 | 15.0% |

| Total, All Races, All Ethnicities | 3,600,913 | 3,597,318 | -3,595 | -0.1% |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates | ||||

The white, non-Hispanic working-age population fell 4.3% (-120,700 people) while the BIPOC working-age population surged 15.0% (+117,105). In the four years before the pandemic (2016-2020), the white working-age population declined just 1.2% while the BIPOC population grew 9.7%. The post-pandemic years marked when the demographic trend reached a tipping point, and employment is now following.

Demographics Is Destiny

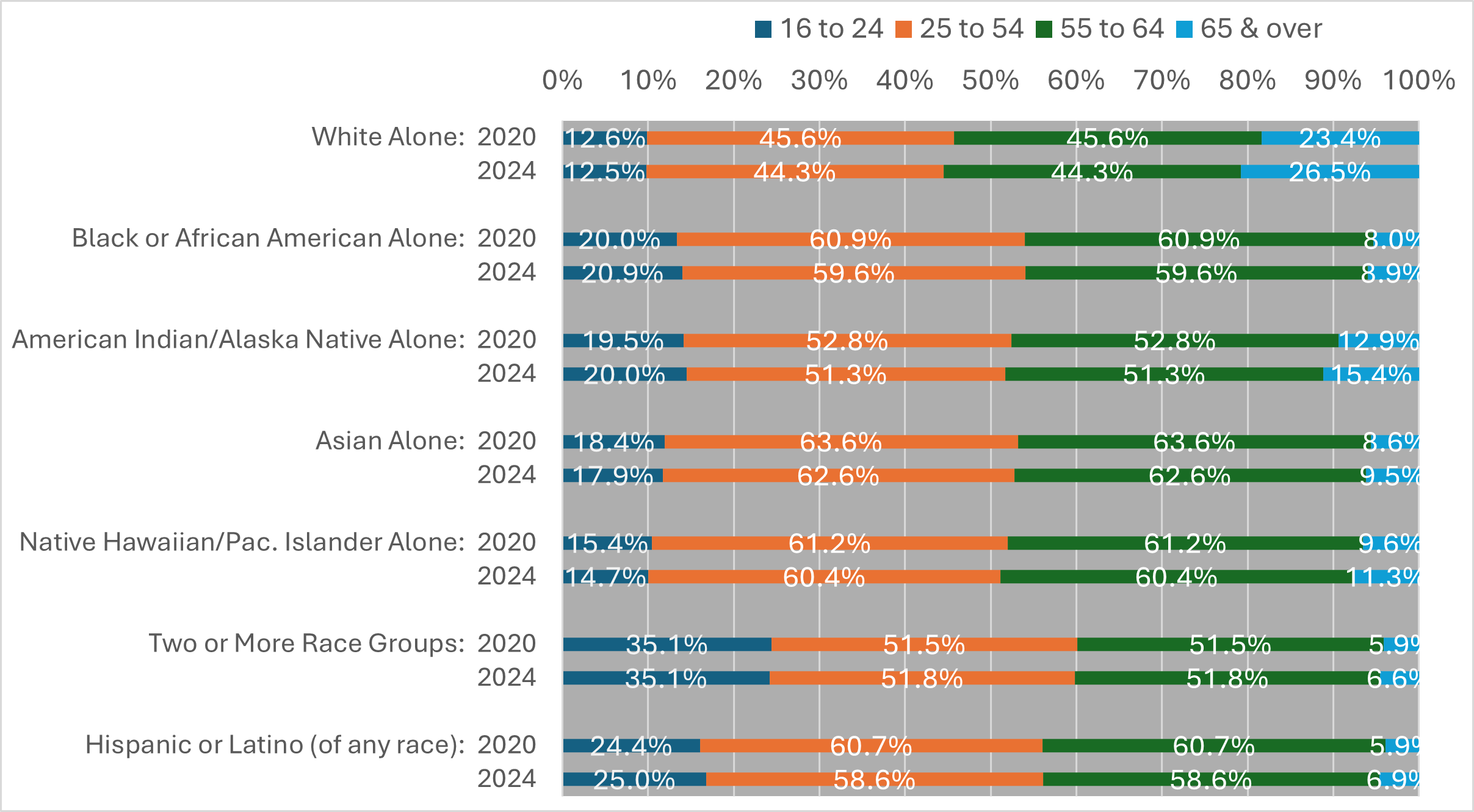

The white, non-Hispanic population is both the largest and oldest cohort of the age 16 and over, or traditional working age population. From 2020 to 2024, the share aged 65 years and over increased from 23.4% to 26.5%. Meanwhile, nearly 30% of Minnesota's 16-24 year old population is BIPOC, compared to just 11% of those 55-64 years of age. As predominantly white workers retire, younger and more diverse workers backfill the jobs. Record-high job vacancy rates during the pandemic recovery created extraordinary opportunities for new labor force entrants, accelerating this inevitable transition (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Minnesota Age 16 and Over Population by Race and Ethnicity and Age Group, 2020 and 2024

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates

Women Surpass Men in Employment Rates

Women now hold 51.0% of Minnesota jobs despite comprising just 50.1% of the working-age population, the result of an outsized employment gain that reverses historical patterns.

Female employment grew 1.2% since 2020 while male employment grew just 0.2%. The number of jobs held by women outpaced male employment before the pandemic as well, growing 7.2% compared to 6.5% for men (Table 3).

| Table 3: Minnesota Employment Change by Age and Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Jobs,

Year to First Quarter |

Change

2015-2020 |

Change

2020-2025 |

|||||

| 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Female | 1,368,546 | 1,467,138 | 1,484,637 | 98,593 | 7.2% | 17,499 | 1.2% |

| 14-18 years | 43,109 | 52,519 | 61,507 | 9,410 | 21.8% | 8,989 | 17.1% |

| 19-21 years | 63,432 | 71,358 | 73,291 | 7,926 | 12.5% | 1,933 | 2.7% |

| 22-24 years | 84,145 | 84,950 | 83,027 | 805 | 1.0% | -1,923 | -2.3% |

| 25-34 years | 305,696 | 315,210 | 301,193 | 9,514 | 3.1% | -14,017 | -4.4% |

| 35-44 years | 270,632 | 311,564 | 329,672 | 40,932 | 15.1% | 18,108 | 5.8% |

| 45-54 years | 301,620 | 282,728 | 285,380 | -18,892 | -6.3% | 2,653 | 0.9% |

| 55-64 years | 237,093 | 263,867 | 246,778 | 26,775 | 11.3% | -17,090 | -6.5% |

| 65 years + | 62,820 | 84,943 | 103,790 | 22,123 | 35.2% | 18,847 | 22.2% |

| Male | 1,337,551 | 1,424,905 | 1,427,653 | 87,354 | 6.5% | 2,748 | 0.2% |

| 14-18 years | 36,938 | 44,741 | 51,435 | 7,803 | 21.1% | 6,694 | 15.0% |

| 19-21 years | 57,452 | 62,948 | 65,019 | 5,496 | 9.6% | 2,071 | 3.3% |

| 22-24 years | 77,779 | 77,636 | 76,827 | -143 | -0.2% | -809 | -1.0% |

| 25-34 years | 308,811 | 314,312 | 295,699 | 5,501 | 1.8% | -18,613 | -5.9% |

| 35-44 years | 281,208 | 314,258 | 322,678 | 33,050 | 11.8% | 8,420 | 2.7% |

| 45-54 years | 291,093 | 274,760 | 274,329 | -16,333 | -5.6% | -430 | -0.2% |

| 55-64 years | 219,709 | 247,928 | 234,693 | 28,219 | 12.8% | -13,235 | -5.3% |

| 65 years + | 64,563 | 88,324 | 106,974 | 23,760 | 36.8% | 18,650 | 21.1% |

| Total, All | 2,706,097 | 2,892,043 | 2,912,289 | 185,946 | 6.9% | 20,246 | 0.7% |

| Source: Quarterly Workforce Indicators | |||||||

This faster pre-pandemic employment growth for women is even more dramatic considering the female population grew 3.4% compared to 5.9% for men (Table 4). Demographic shifts obscure what's happening in the labor market. Case in point: while employment for those age 25-34 and 55-64 declined for both men and women, the population in these age groups declined as well. This represents the massive Millennial and Baby Boomer population cohorts moving into the next age bracket.

| Table 4: Minnesota Population Change by Age and Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (July) | Change 2014-2020 | Change 2020-2024 | |||||

| 2014 | 2020* | 2024 | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Female | 2,266,096 | 2,344,064 | 2,409,852 | 77,968 | 3.4% | 65,788 | 2.8% |

| 14-18 years | 175,759 | 184,194 | 190,544 | 8,435 | 4.8% | 6,350 | 3.4% |

| 19-21 years | 111,667 | 105,257 | 110,560 | -6,410 | -5.7% | 5,303 | 5.0% |

| 22-24 years | 104,893 | 104,801 | 107,985 | -92 | -0.1% | 3,184 | 3.0% |

| 25-34 years | 369,744 | 370,190 | 366,131 | 446 | 0.1% | -4,059 | -1.1% |

| 35-44 years | 332,090 | 366,871 | 387,496 | 34,781 | 10.5% | 20,625 | 5.6% |

| 45-54 years | 379,733 | 332,083 | 325,997 | -47,650 | -12.5% | -6,086 | -1.8% |

| 55-64 years | 360,941 | 381,696 | 354,873 | 20,755 | 5.8% | -26,823 | -7.0% |

| 65 years + | 431,269 | 498,972 | 566,266 | 67,703 | 15.7% | 67,294 | 13.5% |

| Male | 2,206,283 | 2,335,541 | 2,398,452 | 129,258 | 5.9% | 62,911 | 2.7% |

| 14-18 years | 184,064 | 192,903 | 198,837 | 8,839 | 4.8% | 5,934 | 3.1% |

| 19-21 years | 114,756 | 107,935 | 113,403 | -6,821 | -5.9% | 5,468 | 5.1% |

| 22-24 years | 110,248 | 106,645 | 110,698 | -3,603 | -3.3% | 4,053 | 3.8% |

| 25-34 years | 375,347 | 387,457 | 382,283 | 12,110 | 3.2% | -5,174 | -1.3% |

| 35-44 years | 339,392 | 384,822 | 404,000 | 45,430 | 13.4% | 19,178 | 5.0% |

| 45-54 years | 379,298 | 345,325 | 340,589 | -33,973 | -9.0% | -4,736 | -1.4% |

| 55-64 years | 354,388 | 384,312 | 357,761 | 29,924 | 8.4% | -26,551 | -6.9% |

| 65 years + | 348,790 | 426,142 | 490,881 | 77,352 | 22.2% | 64,739 | 15.2% |

| Total, All | 4,472,379 | 4,679,605 | 4,808,304 | 207,226 | 4.6% | 128,699 | 2.8% |

|

* April 1, 2020 Population Estimates Base Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates |

|||||||

Thus, the more revealing story appears in employment-to-population (E/P) ratios. These control for population changes to show what share of each group is employed. However, Tables 3 and 4 are essential to make sense of changes in the ratios.

From 2014 to 2019, female E/P ratios grew 2.2 percentage points (60.4% to 62.6%) while male rates crawled up just 0.4 points (60.6% to 61.0%). By 2019, women's employment to population rate exceeded men's by 1.6 percentage points – likely the first time in modern Minnesota history (Table 5).

| Table 5: Minnesota Employment to Population Ratio (E/P) Change by Age and Sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E/P | E/P Change | ||||

| 2014 | 2019 | 2024 | 2014-2019 | 2019-2024 | |

| Female | 60.4% | 62.6% | 61.6% | 2.2 | -1.0 |

| 14-18 years | 24.5% | 28.5% | 32.3% | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| 19-21 years | 56.8% | 67.8% | 66.3% | 11.0 | -1.5 |

| 22-24 years | 80.2% | 81.1% | 76.9% | 0.8 | -4.2 |

| 25-34 years | 82.7% | 85.1% | 82.3% | 2.5 | -2.9 |

| 35-44 years | 81.5% | 84.9% | 85.1% | 3.4 | 0.2 |

| 45-54 years | 79.4% | 85.1% | 87.5% | 5.7 | 2.4 |

| 55-64 years | 65.7% | 69.1% | 69.5% | 3.4 | 0.4 |

| 65 years + | 14.6% | 17.0% | 18.3% | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| Male | 60.6% | 61.0% | 59.5% | 0.4 | -1.5 |

| 14-18 years | 20.1% | 23.2% | 25.9% | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| 19-21 years | 50.1% | 58.3% | 57.3% | 8.3 | -1.0 |

| 22-24 years | 70.5% | 72.8% | 69.4% | 2.2 | -3.4 |

| 25-34 years | 82.3% | 81.1% | 77.4% | -1.2 | -3.8 |

| 35-44 years | 82.9% | 81.7% | 79.9% | -1.2 | -1.8 |

| 45-54 years | 76.7% | 79.6% | 80.5% | 2.8 | 1.0 |

| 55-64 years | 62.0% | 64.5% | 65.6% | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| 65 years + | 18.5% | 20.7% | 21.8% | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| Total, All | 60.5% | 61.8% | 60.6% | 1.3 | -1.2 |

| Sources: Quarterly Workforce Indicators, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates and author's calculations | |||||

Post-pandemic, the male E/P declined 1.5 points (61.0% to 59.5%) while the female employment rate fell just 1.0 point (62.6% to 61.6%). Women now maintain a 2.1-point employment advantage, and the gap is widening.

This isn't the full story of employment rates by sex. The employment in these E/P ratios includes only wage and salary employment and does not include most self-employment. Men maintain significantly higher self-employment rates, which is explored later in this article, but it represents a fundamental shift in traditional employment patterns.

Understanding Age and Sex Employment Rate Trends

These age and sex differences reveal nontraditional patterns for men, remarkable increases in employment rates among women, employment disengagement for young adults and continued high engagement for teens and seniors.

Teenage employment rates surge. The E/P ratio for 14- to 18-year-old women increased 3.5 points post-pandemic versus 2.5 for men, sustaining strong pre-pandemic growth trends (+4.2 and +3.3 points respectively). While women outpaced men, both show remarkably strong increases among teenagers, with the highest post-pandemic growth among men and second highest among women . This extends to 19- to 21-year-olds as well, with men and women both increasing, albeit not as much as for high schoolers. This reflects an employer solution for acute labor shortages in industries like Retail Trade, Accommodation & Food Service, and long-term care. However, this often-noted strong labor market for teens in the pandemic recovery is revealed to be a continuation from at least five years prior.

Young adult plunge hits both sexes, but women more. Women age 22-24 experienced the steepest decline in E/P of any female cohort (-4.7 points), reversing pre-pandemic gains. Previous research demonstrates that this is related to the shortage of childcare. This appears to still be the case. The post-pandemic drop for men age 22-24 was 3.1 points, a 1.6-point smaller decline, while male E/P dropped more than female E/P for every other age cohort.

Rates of postsecondary enrollment did not increase for either sex, nor was there a relative increase in female enrollment that could account for the greater post-pandemic drop for women (covered in the same previous research). However, we identify increased self-employment in a later section of this article as a major reason.

Employment disengagement extends to career-building years. The E/P for men age 25-34 tumbled 4.6 points (the second largest drop for men by age cohort) after already declining 0.3 points pre-pandemic. The E/P for women age 25-34 dropped 1.6 points, erasing their 1.1-point pre-pandemic gain. Caregiving may be a factor here, but then we'd expect a bigger post-pandemic drop for women than for men. Male E/P has been trending down for a decade now, so this deserves further research.

Men entering mid-career years had the largest decline. The E/P for men age 35-44 plunged 5.1 points, annihilating the 2.1-point pre-pandemic gain. This may be related to the unknown factors surrounding the career-building-years drop, a pattern counter to the traditional male career trajectory, but the trend is of shorter duration so far. The E/P for women age 35-44 dropped 1.0 point, a stark difference that leaves female E/P 4.1-points higher.

Mid-career women are at historic highs. The E/P for women age 45-54 surged 4.2 points to reach 87.5% – the highest employment rate of any cohort, male or female, and for any age. This follows a 4.0-point pre-pandemic increase. Men age 45-54 saw a 0.2 point decline, creating a 7.0-point female advantage.

Prime working age changes have outsized impacts. Before we progress past the so-called "prime working years," it's worth noting that declining E/P rates for men had the biggest overall impact in ages 25 to 54. These age groups have the largest employment, so a decline is most impactful. Men lost the most ground to women within ages 25 to 54. This is often discussed as a social-cultural shift, but it is also likely related to the persistent long-term growth and immense employment in the female-dominated Health Care & Social Assistance sector.

Late-career gains recommence. The E/P of men age 55-64 gained 0.2 points, adding to the pre-pandemic 3.4-point gain. Women age 55-64 gained 1.4 points following a 2.4-point gain. In the prior research from the pandemic to early 2023, women age 55-64 had declined significantly and much more than men. This was attributed to caregiving for aging parents and grandkids. It appears this was a pandemic impact that is partially resolving.

Seniors extend their working lives. E/P ratios rose 1.4 points for women and 0.9 points for men in the 65+ age cohort, confirming that employment growth isn't just from a population that is growing older. Instead, there is increasing work propensity, reflecting delayed retirements, better health, financial necessity, or some combination of all three. Men age 65 years and older maintain the largest E/P advantage over women of any age group (21.8% vs. 18.3%), though both are rising.

Self-Employment Surge Led by Women and Youth

Self-employment rebounded sharply post-pandemic, growing 8.1% from 2019 to 2024 after declining 5.6% from 2014 to 2019. This analysis builds on separate previous analysis of post-pandemic self-employment growth by examining demographics from IPUMS rather than Nonemployer Statistics (Table 6).

| Table 6: Minnesota Self-Employment Change by Age and Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Employment | Change 2014-2019 | Change 2019-2024 | |||||

| 2014 | 2019 | 2024 | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Female | 116,077 | 119,288 | 133,482 | 3,211 | 2.8% | 14,194 | 11.9% |

| 19-21 years | 1,408 | 2,304 | 4,687 | 896 | 63.6% | 2,383 | 103.4% |

| 22-24 years | 1,405 | 3,954 | 6,288 | 2,549 | 181.4% | 2,334 | 59.0% |

| 25-34 years | 12,759 | 17,742 | 16,677 | 4,983 | 39.1% | -1,065 | -6.0% |

| 35-44 years | 21,625 | 20,326 | 24,717 | -1,299 | -6.0% | 4,391 | 21.6% |

| 45-54 years | 29,207 | 25,580 | 28,801 | -3,627 | -12.4% | 3,221 | 12.6% |

| 55-64 years | 30,870 | 30,222 | 29,603 | -648 | -2.1% | -619 | -2.0% |

| 65 years + | 18,803 | 19,160 | 22,709 | 357 | 1.9% | 3,549 | 18.5% |

| Male | 225,688 | 203,481 | 215,303 | -22,207 | -9.8% | 11,822 | 5.8% |

| 19-21 years | 1,871 | 1,671 | 4,685 | -200 | -10.7% | 3,014 | 180.4% |

| 22-24 years | 1,999 | 3,051 | 3,745 | 1,052 | 52.6% | 694 | 22.7% |

| 25-34 years | 28,253 | 20,941 | 22,178 | -7,312 | -25.9% | 1,237 | 5.9% |

| 35-44 years | 36,525 | 38,855 | 36,481 | 2,330 | 6.4% | -2,374 | -6.1% |

| 45-54 years | 55,726 | 39,584 | 45,163 | -16,142 | -29.0% | 5,579 | 14.1% |

| 55-64 years | 61,326 | 56,171 | 48,845 | -5,155 | -8.4% | -7,326 | -13.0% |

| 65 years + | 39,988 | 43,208 | 54,206 | 3,220 | 8.1% | 10,998 | 25.5% |

| Total, All | 341,765 | 322,769 | 348,785 | -18,996 | -5.6% | 26,016 | 8.1% |

| Source: IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org | |||||||

Female self-employment grew 11.9% from 2019 to 2024 (+14,194 workers) – double the 5.8% male growth rate. This continues a longer trend: female self-employment grew 2.8% from 2014-2019 while male fell 9.8%. Men's share of total self-employment declined from 63.0% to 61.7%, though more than 3 out of 5 self-employed are men.

Young Adults Embrace Solo Entrepreneurship – Or Are Pushed into It

The most dramatic shift is the explosive self-employment growth among workers age 19-24, precisely the groups experiencing the steepest E/P declines in traditional jobs . In the analysis above, the E/P includes only wage and salary employment and does not include most self-employment. This part of the analysis focuses on self-employment.

Self-employment for men age 19-21 exploded 180.4% (+3,014 workers) and jumped 103.4% (+2,383) for women. Self-employment for workers age 22-24 also surged: women +59.0% (+2,334), men +22.7% (+694). Combined, these cohorts added 7,745 self-employed workers, accounting for nearly 30% of total statewide self-employment gains. Moreover, the 8,425 net increase in self-employed workers age 19-24 far outstrips the 1,272 net increase in wage and salary employment in Table 3.

Does self-employment offset employment declines? Overall, only the youngest workers (age 19-24) show a meaningful shift to self-employment. For workers age 25 and over, self-employment isn't a safety valve; it is either declining alongside traditional employment or growing only very modestly.

Note that in the rare case where self-employment does offset employment losses, that does not mean that it makes up for the declining E/Ps. Using female age 22-24 as an example, traditional employment fell by 1,923 jobs while self-employment rose by 2,334 workers. So, employment losses were more than fully offset by self-employment.

Yet the E/P plummeted 4.7 points. So, self-employment would have to also overtake population growth to restore E/P. Population increased by 3,883 people, so self-employment was far from offsetting the E/P back to the 2019 level.

This means more women age 22-24 are disconnected from work than pre-pandemic, even with the self-employment growth. Nonetheless, self-employment growth did fill some of the gap.

Next, let's look at which cohorts had declining employment to see how much growth in self-employment offset it. An offset means more are engaged in work than we thought based on the E/P.

Self-employment for 22- to 24-year-old men mostly offset wage/salary job losses. The 694 self-employed increase offset most of the 809 wage/salary jobs lost.

For women aged 25-34, both self-employment (-1,065) and traditional employment declined; so there was no offset.

Finally, for 25- to 34-year-old men, self-employment added just 1,237 workers while traditional employment fell by 18,613 jobs, presenting a very slight offset.

Mid-Career and Senior Self-Employment: Growing Numbers, Diverging Patterns

While young adults show dramatic percentage gains, middle-aged and senior workers account for the largest absolute increases, and men top the list. For example, men age 65+ added the most self-employed, but had the fourth fastest growth. This likely reflects Baby Boomers transitioning from traditional retirement to part-time consulting, contracting, or small business ownership. It is informative to view the top five in order of numeric gain:

- Men 65+: +10,998 (+25.5%)

- Men 45 to 54: +5,579 (+14.1%)

- Women 35-44: +4,391 (+21.6%)

- Women 45-54: +3,221 (+12.6%)

- Women 65+: +3,549 (+18.5%)

This shows that mid-career women (age 35-54) showed strong self-employment gains as well. Self-employment surged 21.6% for women aged 35-44, while male self-employment in this group fell 6.1%, a striking difference. Combined with E/P data, women age 35-44 presents a unique story. This cohort added jobs in both wage/salary and self-employment, while the E/P declined a slight -0.1 points. Adding self-employment gains to job gains overcomes the decline in E/P. This is the only group that restored E/P from a gain in self-employment, but there was no employment decline to offset.

Among workers age 45-54, both sexes increased self-employment (women +12.6%, men +14.1%), but women's E/P rose 2.4 points versus men, which rose by only 1.0 point. Combined with the fact that women age 45-54 have the highest E/P, this suggests that this cohort combined traditional and self-employment while mid-career men may have substituted one for the other.

Workers ages 55-64 represent the only age group experiencing meaningful self-employment losses for both sexes. Female self-employment declined 2.0% (-619 workers) while male self-employment plummeted 13.0% (-7,326 workers). This suggests late-career workers tend to retire from self-employment due to the physical or financial demands of running a business or working as an independent contractor in their 60s. Or, maybe this group moves into wage and salary employment to better save toward retirement.

In contrast, seniors are increasingly working for themselves. Self-employment among people aged 65 years and older increased by 14,547 from 2019 to 2024. This may have been a financial necessity, a lifestyle choice or a way to ease into retirement gradually.

Conclusion: A Fragmenting Labor Market Demands New Strategies

Minnesota's post-pandemic workforce transformation isn't a temporary disruption; it's the acceleration of demographic inevitabilities colliding with a restructured labor market.

The data reveals five fundamental shifts:

1. Demographics are destiny. The white, non-Hispanic working-age population declined 4.3% while the BIPOC population increased 15%. This made workforce diversity growth inevitable; pandemic recovery dynamics simply accelerated it. As predominantly white Baby Boomers retire, increasingly diverse Millennials and Gen Z backfill the jobs. This trajectory will continue.

2. Traditional sex-based employment patterns have reversed. Women now outpace men in employment rates – a historic first – with the gap widening post-pandemic. Mid-career women (35-54) have reached unprecedented employment levels, while prime-working-age men (25-44) experienced employment disconnection. Understanding why 25- to 44-year-old men are leaving employment while women 35-54 increasingly engage requires further study. Women entering the workforce have been a long-term driver of employment growth in the state. However, men in the prime working years are now a potentially available workforce that could again be tapped.

3. The labor market is polarizing by age. The combination of working teenagers and working seniors – both groups with traditionally lower workforce participation – fits the increasing diversity theme reshaping Minnesota's labor market. And as shown in Figure 1, youth is the most racially and ethnically diverse age cohort.

However, as teenagers and seniors surge in employment, young adults from 22-34 years of age have begun to retreat. This creates staffing in entry-level and consulting roles but scarcity in prime career-building years. The 22-24 age cohort, which shows the steepest declines, represents lost talent and productivity. Employers who were already adept at recruiting and training youth before the pandemic had an advantage in the pandemic recovery and will have an ongoing advantage. Young adults are not as engaged in employment as in the past, representing a potentially available workforce for the employers that can figure out how to engage them.

4. Self-employment is exploding among young adults – but it's not enough. Workers age 19-24 more than doubled their self-employment, but this only partially offsets traditional employment losses. Whether this represents entrepreneurial opportunity or desperation matters; if young adults turn to gig platforms because traditional employment is inaccessible, Minnesota is fragmenting into a two-tier labor market with fewer pathways to career stability.

Implications for Action

These shifts demand strategic responses:

For employers: Competition for talent now means competing across formerly distinct talent pools. The workers available aren't the same as workers hired a decade ago. Recruitment, retention and development strategies built for a predominantly white, male, prime-age workforce are becoming obsolete. Employers can embrace workforce diversity not as a compliance exercise, but as a business necessity.

For workforce development: Programs designed for traditional employment relationships miss the fragmenting reality. Young adults need pathways beyond gig platforms. Prime-age men need re-engagement strategies. Mid-career women need support sustaining their remarkable momentum. One-size-fits-all approaches won't work.

For policymakers: Social safety nets, employment regulations, healthcare and retirement benefits are designed for traditional employer-employee relationships. When the increase in young adult self-employment far outstrips gains in wage and salary employment, those assumptions are challenged. Leaders may need to rethink protections, benefits and support systems for an increasingly self-employed workforce.

For economic development: Minnesota's economic future depends on engaging the workers who are here: and they are increasingly diverse, increasingly female, increasingly young or old and increasingly self-employed. Economic development strategies that don't recognize this reality will struggle to succeed or create maximum impact.

The pandemic didn't create these trends, but it revealed and accelerated them. Minnesota's workforce of 2025 is fundamentally different from 2019. The question isn't whether to adapt, but how quickly we can.