Building a system that meets the state digital accessibility standard for all users.

1/26/2021 7:00:00 AM

By: Michael Lind Varien, Senior Project Analyst with the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources

The Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) is currently designing, developing, and implementing an online proposal and grant management system. One of the objectives is to build a system that meets the state digital accessibility standard for all users, including:

The LCCMR is a legislative commission made up of seventeen members, including ten legislators and seven citizens. The commission recommends projects to the legislature to receive funding from the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund (ENRTF).

Our plan was to design, develop, and implement an online proposal and grants management system. It would:

The aim was to move our paper-based process to an online system. A primary goal was to shift from providing accommodations when requested to accessibility for all users. We are committed to upholding the state standard for accessibility to make information accessible to all Minnesotans.

Early on, the staff’s initial questions set the stage for incorporating accessibility throughout the project. These included:

IT is not the area of expertise for the commission’s five staff members. While we make documents accessible and understand the needs of some people that access our body of work, we have limited expertise to address digital accessibility.

As a joint commission of the legislative branch, the LCCMR does not have a designated IT department. Most IT and accessibility needs are managed in-house; in other words, by my four colleagues and me. However, we do have limited access to various resources, such as:

When we began this project there was no statute, but since beginning this project, the legislature passed law that requires the legislature to comply with digital accessibility standards adopted for state agencies. Our experience had also shown us that any system we built would need to meet accessibility standards.

We started with our most common accommodation needs and used that to help guide us through the planning and development of the system. We needed a system that would reduce the costs of our current accommodation process.

There were many details that we simply did not know, such as what specific accessibility criteria to include in a Request for Proposal (RFP) for prospective system developers. This is why we asked the Office of Accessibility for help. In preliminary meetings with the Office of Accessibility and members of the interagency accessibility working group we discussed:

When we drafted the RFP we wanted to ensure that we communicated the importance of digital accessibility for both the system and any documents generated by the system. To do this we included the following statements in four distinct parts of the RFP: background, scope of work, deliverables, and an appendix.

“Labor-intensive manual remediation is at times required to enable documents to comply with electronic accessibility standards.”

“Ability to meet accessibility standards and needs for system user interface and data and document uses.”

“Responders must complete the Voluntary Product/Service Accessibility Templates, VPAT, (508 VPAT and WCAG 2.0 VPAT). See the 'Procurement' tab and go to the 'Products' tab then go to 'VPAT 2.0 site (via ITIC)'. This component of the Proposal should demonstrate the Responder’s capabilities in regards to supporting the State of Minnesota’s accessibility statute. The Responder can also provide their Accessibility Maturity Roadmap that spells out how and when accessibility improvements are incorporated into their solution. Submitted VPAT(s) will be incorporated into the contract that results from this solicitation, if awarded.”

B. System Interface

“19. System interface should be ADA (Americans with Disability Act) accessible utilizing or compatible with adaptive technologies according to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 of the State of Minnesota's Accessibility Standard (PDF)."

One of the most important steps we took was early review of the system wireframes by accessibility experts and users. This preliminary review was critical to the success of this project. It avoided the cost of building inaccessible parts of the system that would later need reworking, and it raised everyone’s understanding of digital accessibility. Here is how that worked:

“As a vendor it was extremely beneficial to discuss how accessibility standards play into the design prior to development. It truly felt like we were all one team working towards a common goal.”

– Brian Fisher, Houston Engineering Inc.

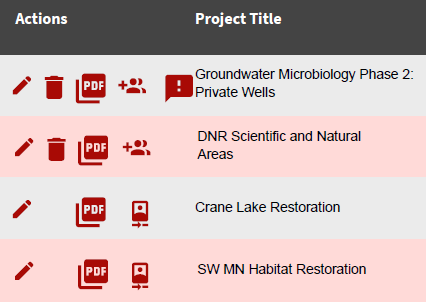

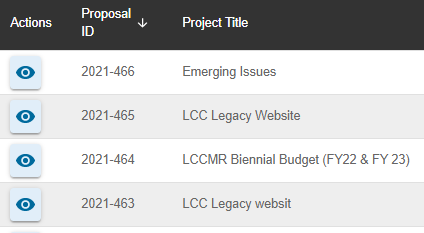

The following is an example from these meetings with the experts. We originally designed a table in the wireframes and thought this would allow users to access everything in the system from one place. Users could:

As a staff, we thought we had designed the ultimate user interfaces for our system.

This table is great for me, but that is only because I can see, I know what the icons are, and I can use a mouse and a keyboard. However, when we met with the accessibility experts, they all chuckled because, from an accessibility perspective, this would be difficult to make both accessible and usable.

As a result of wireframe review by accessibility experts, we moved most actions to more appropriate locations throughout the system. This made the table simpler, and the system more dynamic. This also avoided costly rebuilds, and made the system overall more usable for everyone.

We included accessibility testing as part of the user acceptance testing (UAT) for the various users and parts of the system. We coordinated with the Office of Accessibility, and developed specific test plans that allowed experts to strategically test specific functionality and parts of the system.

Additionally, LCCMR staff were trained to test common accessibility aspects including:

The experts focused on more difficult testing. LCCMR staff covered simpler tests, and got on-the-job training that would carry over to other areas.

The Office of Accessibility collated testing results, wrote a report of findings, and met with the vendor and LCCMR staff to address any barriers and possible solutions.

Successes included the benefits of collaboration, training, and planning for accessibility from the start. We also learned some lessons, including:

Meeting the state digital accessibility standard is not simply checking a box. It is, and should be, a significant part of any plan to build an online system.

In the future, we would plan for more time and resources to design, build, and test for accessibility. To do this we recommend user acceptance testing for a typical user and for accessibility to ensure the system works for everyone. Plan a parallel testing and review timeline that aligns standard UAT and accessibility testing such that they each have distinct testing periods and milestones.

We are actively using the completed parts of the system while design, build, and testing the remaining functionality continues. We have issued the 2022 RFP for ENRTF funding, which will be the second year using the system for proposals. Initial feedback from testers and users suggests that we have built a system that is more accessible for all users. Comments from project managers and grantees include how easy it is to use, navigate, and work in this online system. We believe including accessibility from the start is helping us build a system that is more user-friendly and accessible for all.

Would you like to learn more about the accessibility work being done by Minnesota IT Services and the State of Minnesota? Once a month we will bring you more tips, articles, and ways to learn more about digital accessibility.

Accessibility