The 1990s: More, But Slow, Progress.

From Integration to Inclusion. From Placement to Outcome.

In 1970, only one in five students with disabilities was educated in American schools. In 1993, fewer than 7% of school-aged children with developmental disabilities were educated in general education classrooms. The struggle had shifted over the years from getting children with disabilities into public schools to supporting them to learn in the classrooms of neighborhood schools.

In 1997, IDEA was amended. It formalized a shift in thinking that was kick started by Madeleine Will back in 1986. In 1986, Ms. Will, and many others, observed that little had changed in the schools of the nation since 1974 and 1977 when P. L. 94-142 and P. L. 93-380 required integration into the least restrictive environment.

Many educators, parents, and lawmakers agreed that there were unresolved problems that warranted attention. Educational outcomes remained less for students with disabilities than for other students, often leaving them unprepared to graduate and subsequently transition to the community, higher education and the workplace. For example, according to information compiled by the Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS):

- Many students with disabilities are still excluded from the curriculum and assessments used with their nondisabled peers, limiting their possibilities of performing to higher standards.

- In the 1997–98 school year, only 25 percent of students ages 17 and older with disabilities graduated with a high school diploma. Graduation rates varied by state, ranging from 6.8 percent to 45.5 percent.

- Twice as many children with disabilities drop out of school.

- Dropouts rarely return to school, have difficulty finding jobs, and often end up in the criminal justice system.

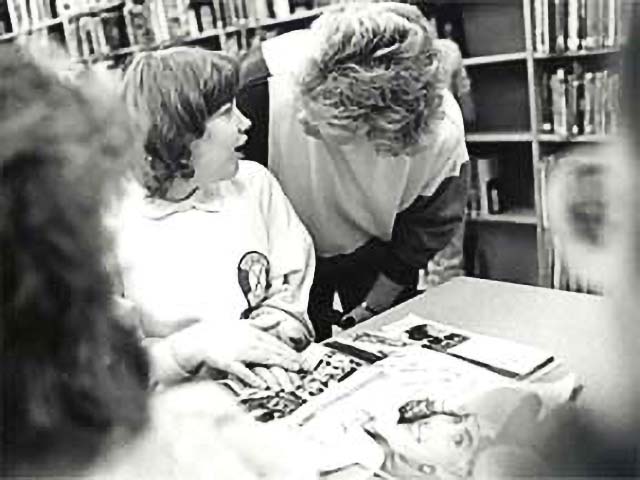

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights observed that for more than 20 years (1975 to 1997), the EHA/IDEA remained largely unchanged..

- Between 1979 and 1994, a series of amendments to the EHA refined and increased the number of discretionary programs in personnel preparation, research, demonstration and technical assistance.

- Amendments were offered in 1986 (P.L. 99-457) which added a mandate for preschool programs for age 3-5 and planning for early intervention programs for infants and toddlers with disabilities.

- In 1990, the EHA/94-142 was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (P. L. 101-476) and amended. In addition to changing terminology from "handicap" to "disability", it mandated transition services and added autism and traumatic brain injury to the eligibility list.

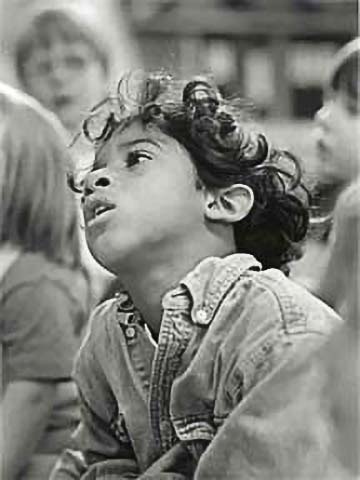

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

The Challenge of Compliance

Throughout the history of the IDEA, one of the biggest challenges has been compliance. The intent of P. L. 94-142 was bolstered in 1994 when the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Special Education Programs issued policy guidelines stating that school districts cannot use the lack of adequate personnel or resources as an excuse for failing to make a free and appropriate education available, in the least restrictive environment, to students with disabilities. This guideline, however, is similar to the 1972 court ruling that said much the same thing.

Schools and local authorities continued to take their time to implement the law. Many schools and districts have been educating students with disabilities in segregated settings for years, yet families often have to fight to get their children into general education classrooms and inclusive environments.

This in spite of the fact that court cases have determined that families do not have to prove to the school that a student with disabilities can function in the general classroom.

In Oberti v. Board of Education of the Borough of Clementon School District (1993), for example, the U.S. circuit court determined that the neighborhood school had not supplied a student with the supports and resources he needed to be successful in an inclusive classroom.

The judge also ruled that the school had failed to provide appropriate training for his educators and support staff. The court placed the burden of proof for compliance with the law's inclusion requirements squarely on the school district and the state instead of on the family.

In other words, the school had to show why this student could not be educated in general education with aids and services, and his family did not have to prove why he could. The federal judge who decided the case stated, "Inclusion is a right, not a special privilege for a select few."

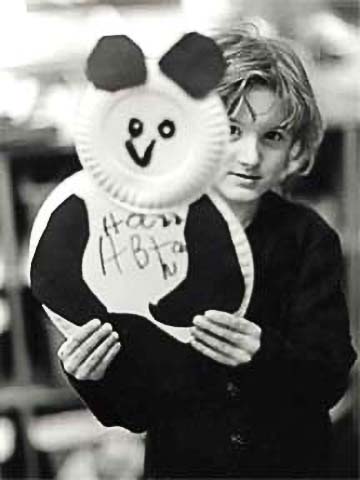

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden.

Amendments in 1997 Make Significant Improvements

In 1997, more significant amendments were passed "to clarify, strengthen and provide guidance on its implementation." According to the Commission on Human Rights,

The 1997 amendments placed emphasis on education results and improved quality of special education and included tools for enforcement. Of particular concern at the time was the integration of students with disabilities into general schools and classrooms. The revised bill also addressed school discipline, giving educators more flexibility in disciplining children with disabilities, while at the same time directing them to act in anticipation of challenging behavior rather than punishing children for misbehavior associated with their disabilities.

IDEA 2004 (P. L. 108-46) passed in December 2004, and the new regulations were released in August 2006. The 108th Congress found that "Since the enactment and implementation of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, this title has been successful in ensuring children with disabilities and the families of such children access to a free appropriate public education and in improving educational results for children with disabilities. However, the implementation of this title has been impeded by low expectations, and an insufficient focus on applying replicable research on proven methods of teaching and learning for children with disabilities."

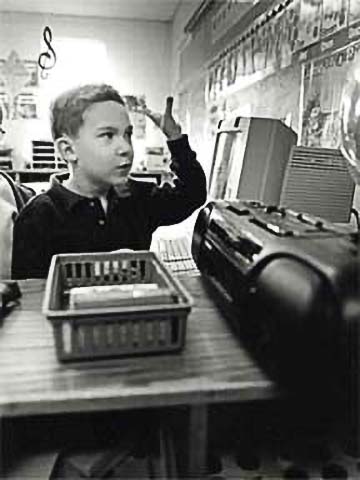

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

IDEA 2004

IDEA 2004 raises the standards of performance and requires schools to use research-based instruction and provide more intensive special education services, and requires teachers to have "the skills and knowledge necessary to improve the academic achievement and functional performance of children with disabilities, including the use of scientifically based instructional practices, to the maximum extent possible."

There is general consensus that the IDEA has made tremendous strides toward improving the education of students with disabilities. Today, more than six million students benefit from IDEA funding, and the integration of students has proven critical to students who have disabilities, as well as those who do not.

It is commonly believed that integration fosters understanding and tolerance, better preparing students of all abilities to function in the world beyond school. According to one advocacy group IDEA ensures that children with disabilities may attend public schools alongside their peers.

In addition, post-school employment rates for individuals served under the IDEA are twice those of older adults with similar disabilities who did not have the benefit of the IDEA.

Further, postsecondary school enrollments among individuals with disabilities have also increased; the percentage of first-year college students reporting disabilities has more than tripled since 1978.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

The Key Concepts of IDEA (1997 and 2004) are:

Zero Reject. A free appropriate public education is available to all children with disabilities, residing in the State between the ages of 3 and 21, inclusive, including children with disabilities who have been suspended or expelled from school. In IDEA 2004, such a free appropriate public education emphasizes "special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living."

Non-discriminatory evaluation. Determine whether the student has a disability and, if so, what needs the student has for special education and related services. In IDEA 2004 provisions are made for alternative assessments. There are also provisions to prevent the over-representation of children from minority groups in special education.

Appropriate education: Develop and implement an Individual Education Program (IEP). The 1997 amendments included an increased emphasis on participation of children with disabilities in the general curriculum and the involvement of regular education teachers in developing, reviewing and revising the IEP. IDEA 2004 continues this emphasis with significant changes to the process. IDEA 2004 also adds an emphasis on preparing young people for post-secondary/further education, and on improving the child's academic achievement and functional performance while in school. Transition plans are required at age 16 rather than age 14 under IDEA 1997.

Least restrictive environment: Educate a student with a disability, to the maximum extent appropriate for the student, with students who do not have disabilities. in IDEA 2004, this was expressed as follows – To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the general educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in general classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Procedural due process: Procedures that schools and parents have at their disposal to hold each other accountable. The 1997 and 2004 amendments make mediation available as a means for more easily resolving parent-school differences.

Parent participation: The 1997 and 2004 amendments enhance parent participation in eligibility and placement decisions. In IDEA 2004, schools must obtain informed parental consent before providing special education and related services. If parents refuse, the school district may not use procedures such as mediation and due process in order to provide services.

Outcomes and Standards: The 1997 amendments required states to include students with disabilities in state and district-wide testing programs (with appropriate accommodations when necessary); and establish performance goals and indicators for students with disabilities. The 2004 amendments place an increased emphasis on academic achievement and functional performance. The 2004 amendments are coordinated with the No Child Left Behind Act.

The 1997 IDEA called for major re-orientations in programs. Gartner, for instance, compared programs in the New York City Public School before and after the 1997 Amendments.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Comparing Pre-1997 Amendments and Post-1997 Amendments

| Pre-1997 Amendments | Post-1997 Amendments |

|---|---|

| Focused on special education services. | Focuses on strategies to maintain students in general education programs. |

| Avoided focusing on the integration of special education services in the general education environment. | Encourages a general education environment that includes an array of services designed to meet the needs of students with disabilities. |

| Relied on a system of labeling, categorizing, and placing students according to disability. | Emphasizes the unique attributes of each student by requiring non-categorical special education services. |

| Supported self-contained and segregated educational programs. | Supports developing and implementing innovative instructional models that increase the opportunities for students with disabilities to participate in the general education classroom. |

| Determined service placement according to category of disability; students often placed outside their home school district. | Determines service placement according to the unique needs of each student, emphasizing delivery in the home school district. |

Least Restrictive Environment = Educational Placement. Inclusion = Educational Outcome.

In the late 1980s and more energetically in the 1990s, the term "inclusion" came to be recognized as the desired approach to education. Inclusion more accurately embraced the full meaning of IDEA 1997 compared to "integration", and certainly more than "mainstreaming". The literature exploded with books and definitions that identified a more powerful perspective.

Another term for education which is inclusive is supported education, meaning one educational system for all students. Successful schools regard all students as rightful members of the school they would attend, and the class(es) in which they would participate if they did not have disabilities. Each student is provided instructional curricula to meet their individual needs and learning styles.

Inclusion – The practice of providing an education for a child with disabilities within the general education classroom. Supports include Universal Design for Learning (UDL, which is making curriculum accessible), differentiation (making education work for everyone) and individual accommodations needed by that student. Inclusion typically takes place at the student's neighborhood school.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Inclusive education has six clearly stated beliefs and principles that consistently underpin practice. These principles are:

- All children can learn.

- All children attend age-appropriate general educational classrooms in their local schools.

- All children receive appropriate educational programs.

- All children receive a curriculum relevant to their needs.

- All children participate in co-curricular and extra-curricular activities.

- All children benefit from cooperation and collaboration among home, school and community.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Defining School Inclusion

As part of a larger study, authors of relevant literature were asked to submit their definition of school inclusion. The content of these definitions was analyzed using qualitative methodology, and 7 themes emerged:

- placement in natural typical settings;

- all students together for instruction and learning;

- supports and modifications within general education to meet appropriate learner outcomes;

- belongingness, equal membership, acceptance, and being valued;

- collaborative integrated services by education teams;

- systemic philosophy or belief system;

- meshing general and special education into one unified system.

Unless services for students with significant disabilities reflect all of the first 5 themes, those services cannot be defined as reflecting school inclusion.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D

Everyone Belongs

A major underpinning of the idea of inclusion is that Everyone Belongs. The continuum and least restrictive environment concepts, by their nature, encourage all kinds of assumptions about the "placement needs" of students with various types of challenges.

Inclusion starts with the assumption that all children belong in the general classroom with their age peers in the school where they would typically go if they were not disabled. As Doug Biklen has pointed out, it is important to presume competence in all students. Never assume, for instance, a student who is not able to speak is unable to understand and learn. As Jeff and Cindy Strully said about their daughter Shawntell:

We just don't know what people are thinking when they have no reliable and consistent communication system. One day maybe Shawntell will have a communication system/method which will allow her to tell us what she is thinking. Until that time, we want everyone to talk to her and act as if she understands even though we may not know for sure. This is the high road to take on behalf of Shawntell.

As confirmed by Doug Biklen, Jeff Strully and Cindy Strully, the least dangerous assumption is to presume competence in all students.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden