The 1980s: Continued Slow Progress, the Regular Education Initiative

The promise of the "least restrictive environment" was great. Progress, however, was not. The system was not adjusting to the new requirements. The placement of students in less and more restrictive environments changed little.

On the issue of the system adjusting to new requirements, The United States General Accounting Office challenged the system to make substantive changes if the requirements of P. L. 94-142 were to be met within a decade of its passing.

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 requires States to make free appropriate public education available for all children age 3 to 18 by September 1, 1978.

If this goal is to be met by at least the mid-1980s, the Department of Education and the Congress need to resolve problems with:

- determining the number of children needing services,

- unclear eligibility criteria,

- individualized education programs,

- sufficiency of resources, and

- program management and enforcement.

It was only in 1984 that the last state, New Mexico, decided to participate in federal funding through P. L. 94-142 and IDEA.

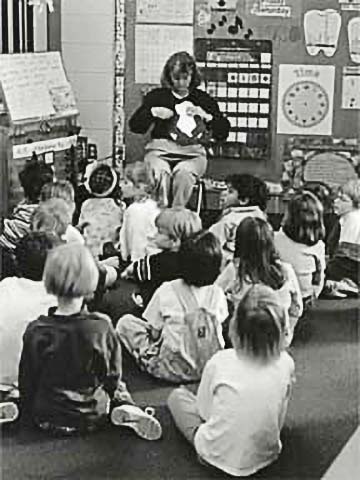

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

On the issue of student placement in the least restrictive environment, there was little change.

- In 1985-86, 25% of students with disabilities spent most of their time in general classes, 44% in resource rooms, 25% in special classes, and 5% in separate schools and residential programs. This distribution was basically the same as that in 1975 when P. L. 94-142 was passed.

- An analysis of U.S. Department of Education reports found that in the years between 1977 and 1990, placements of students with disabilities changed little. By 1990, for example, only 1.2 percent more students with disabilities were in general education classes and resource room environments: 69.2 percent in 1990 compared with 68 percent in 1977. Placements of students with disabilities in separate classes declined by only 0.5 percent: 24.8 percent in 1990 compared with 25.3 percent in 1977. And students with disabilities educated in separate public schools or other separate facilities declined by only 1.3 percent: 5.4 percent of students with disabilities in 1990 compared with 6.7 percent of students with disabilities in 1977.

Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Amy Rowley

A free appropriate public education consists of instruction designed to meet the child's unique needs with support services so the child can "benefit" from the instruction. Nothing requires services to "maximize each child's potential." https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/458/176

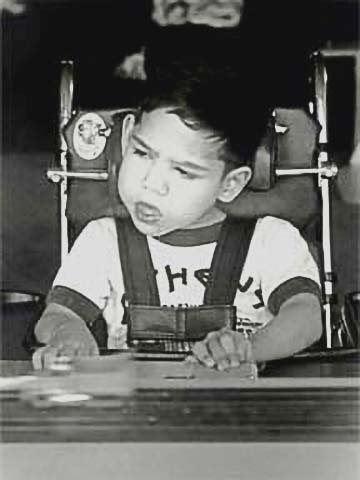

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden.

The IDEA and court cases supported a change in direction that did not appear to be unfolding. For instance, in 1983, Roncker v. Walter challenged the assignment of students to disability specific programs and schools. The ruling favored inclusion and found that placement decisions must be determined on an individual basis.

It is not enough for a district to simply claim that a segregated program is superior. In a case where the segregated facility is considered superior, the court should determine whether the services which make the placement superior could be feasibly provided in a non-segregated setting (i.e., regular class). If they can, the placement in the segregated school would be inappropriate under the act (IDEA). (Roncker v. Walter, 1983, at 1063)

Nevertheless, unfortunately, there were many indications that practices continued to violate the purpose of the IDEA and court decisions.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

The Regular Education Initiative: The Roots of Inclusion

In 1986, however, there was a major shift in the way educators began to think about special education and general education.

Madeleine Will was Assistant Secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, U.S. Department of Education. She was (and is) also the mother of Jon Will who at the time was a teenager with Down syndrome. She brought a new perspective to the federal government and built on the ground work laid in the late 1970s and early 1980s for more and more students to be educated in general classrooms.

Madeleine Will raised concerns about some unintended negative effects of special education "pull out" programs. "Pull out programs" refer to resource rooms and special class placements. She noted that, in the ten years since P. L. 94-142, there had been little change in the distribution of students along the continuum.

The IDEA and court cases supported a change in direction that did not appear to be unfolding. For instance, in 1983, Roncker v. Walter challenged the assignment of students to disability specific programs and schools. The ruling favored inclusion and found that placement decisions must be determined on an individual basis.

It is not enough for a district to simply claim that a segregated program is superior. In a case where the segregated facility is considered superior, the court should determine whether the services which make the placement superior could be feasibly provided in a non-segregated setting (i.e., regular class). If they can, the placement in the segregated school would be inappropriate under the act (IDEA). (Roncker v. Walter, 1983, at 1063)

Nevertheless, there were many indications that practices continued to violate the purpose of the IDEA and court decisions, therefore many schools districts were not following the laws that established them in the first place.

The debate centered around four key issues. These issues included

- the exclusion of many students who needed special educational support;

- the withholding of special programs until the student failed rather than making specially designed instruction available earlier to prevent failure;

- no support for promoting cooperative, supported partnerships between educators and parents;

- and using pull-out programs to serve students with disabilities rather than adapting the general education program to accommodate their needs.

Ultimately, the Regular Education Initiative (REI) caused significant changes in the entire approach to special education. A new term, inclusion, and a new technique, collaboration, evolved.

There was considerable resistance to these concepts. Many charged that integration and mainstreaming basically meant dumping. The controversy is reflected in the efforts of Doug Biklen and his colleagues to be very clear about what integration did and did not mean.

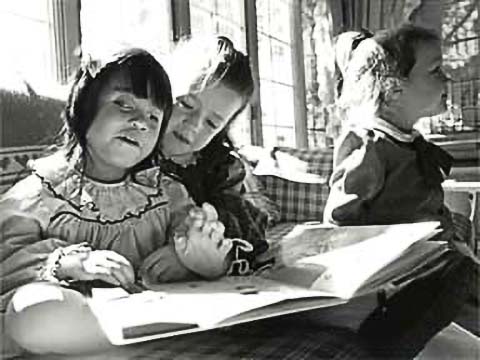

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Integration DOES mean:

- Educating all children with disabilities in general school settings regardless of the degree or significance of their disabilities.

- Providing special services within the regular schools and classrooms.

- Supporting general teachers and administrators.

- Involving students with disabilities in as many academic classes and extracurricular activities as possible, including math, social studies, language arts, reading, art, music, gym, field trips, assemblies, and graduation exercises.

- Arranging for students with disabilities to use the school cafeteria, library, playground, and other facilities along with non-disabled students.

- Encouraging friendships and social relationships students with and without disabilities.

- Arranging for students with disabilities to receive their education and job training in general community environments when appropriate

- Teaching all children to understand and accept human differences.

- Placing children with disabilities in the same schools they would attend if they did not have disabilities.

- Taking parents' concerns and preferences about integration seriously.

- Providing an appropriate Individualized Educational Program (IEP).

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Integration does NOT mean:

- "Dumping" students with disabilities into general programs without preparation or supports. Ongoing supports such as co-planning, Universal Design for Learning, differentiation, accommodations and co-teaching should exist.

- Locating special education classes in separate wings at a general school.

- Grouping students with a wide range of disabilities and needs in the same program.

- Ignoring children's individual needs.

- Exposing children to unnecessary hazards or risks.

- Placing unreasonable demands on teachers and administrators.

- Ignoring parents' concerns.

- Isolating students with disabilities in general schools.

- Placing older students with disabilities at schools for younger children or other non age-appropriate settings.

- Maintaining separate schedules for students in special education and general education.

As the concepts of integration and inclusion were being discussed in the context of IDEA, other challenges were in process at the post-secondary education level.

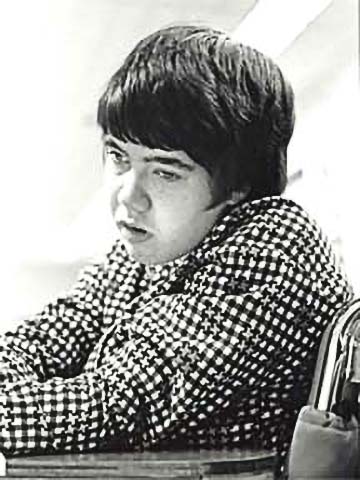

Photo courtesy Mary Ulrich

In the midst of debates surrounding the original 1988 Americans with Disabilities Act, unrest was underway on the campus of Gallaudet University in Washington, DC. Gallaudet University is the only university where all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate deaf and hard of hearing students. In 1988, students protested the University Board's decision to appoint a hearing president. An interview with Dr I. King Jordan, the only deaf President in the history of Gallaudet University, reflects on those moments: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06cr0dz

Photos: Lou Brown

Photos: Images from the 1980s