Real Work: The Development of Real Jobs in Typical Work Settings

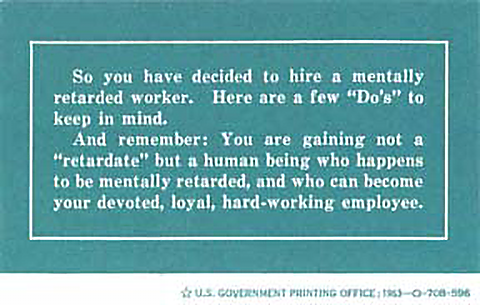

Disclaimer: The language used to describe people with developmental disabilities has changed over the past 50 years. In the earlier decades of this time period, terms and language that are now considered disrespectful and offensive, were acceptable.

As our field and society have come to recognize and urge the use of "people first" language and more respectful words to describe people with disabilities in spoken and written language, terms such as "retarded," "handicapped," "trainable," and "educable" have been replaced in many instances.

The remnants of what is now considered unacceptable language and terms may still be found in references to official governmental bodies (i.e. President's Panel on Mental Retardation), organizations that were founded during these earlier years, federal laws, reports (i.e. Community Residences for Mentally Retarded Persons), case law, and quotations.

The 1950s: Day Programs to Prevent Institutionalization

In the 1950s, parents and activists worked towards building community rehabilitation programs and day activity centers as an alternative to their sons and daughters staying at home or living in institutions.

The programs were supposed to provide work and socialization time. They were a place of safety and support that allowed adults to stay out of institutions. For many parents, then and now, the reliability of a consistent day program was a source of comfort.

The "safety net" was in place.

Produced by the Rehabilitation Continuing Education Program, Region 7, University of Missouri 2004

Supplemental Documents from RSA

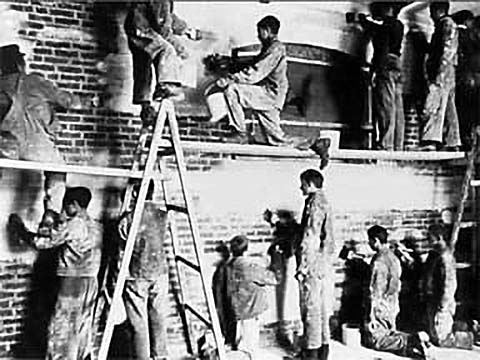

Image credit: Virginia State Library (found in Feeble Minded in our Midst by Steven Noll, 1995.)

Sheltered Workshops and Day Activity Programs Begin

The President's Committee on Mental Retardation summed up the development of sheltered workshops and day activity programs in the 1950s.

During the early years of the National Association for Retarded Children, much of the effort of many local associations was directed toward conducting demonstration educational programs for school age children with disabilities. With the successful demonstration of educating these children, the public schools began to assume this responsibility for education.

As a result, an interesting situation was created. Many local associations which were organized to provide educational services found that their major purpose was accomplished. Consequently, many associations turned their attention toward other problems the above school age group with disabilities, the pre-school age group, and those with profound disabilities of all ages. Because of this situation, community provisions for the post-school age groups gained in popularity (PCMR 1972).

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Federal Funding = More Workshops

Federal funding made these developments possible. The 1943 Amendments to the Vocational Rehabilitation Act made people with mental retardation or emotional disabilities eligible for rehabilitation services along with people with physical disabilities.

The 1954 amendments to the Vocational Rehabilitation Act (P.L. 83-565) established research and demonstration project funding, and funding for construction of rehabilitation facilities. The financing arrangements allocated funds to states based on a formula reflecting population and per-capita income.

Since 1954, the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation has supported research on all aspects of rehabilitation, including the social and occupational adjustment of people with mental disabilities.

Demonstration techniques for rehabilitating these individuals have been undertaken… Community rehabilitation agencies have extended and strengthened their facilities and resources for serving them… From 1954 through 1961… the estimated funds for vocational rehabilitation of people with mental disabilities increased 15-fold (PCMR). That expanded funding led to the rise of over 1,000 workshops across the country.

The workshops varied considerably but had two common objectives:

- to train adults who proved "suitable" for competitive employment, and

- to provide long term or permanent employment for adults whose work skills were "not minimally acceptable to competitive industry."

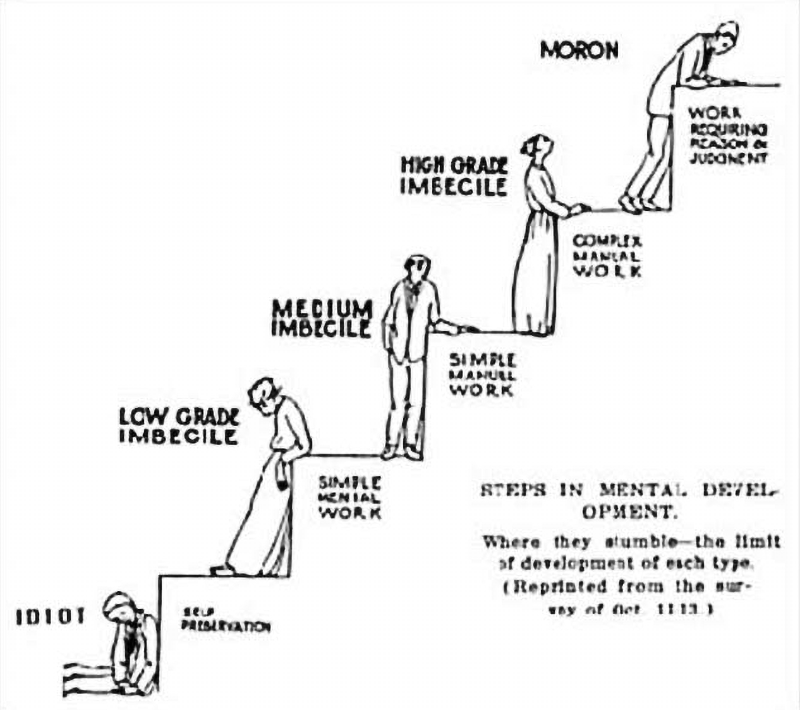

Those who were considered "placeable" after training were classified as "deferred placeable" while those who were seen as only able to work in sheltered settings were classified "sheltered employable". In the language of the day, the "deferred placeable" were in the "high educable range" while the "sheltered employable" were in the lower educable and high trainable range.

Day Activity Programs

Two pressures then led to the development of day activity programs.

- First, as workshops gained experience they saw the need for a different kind of program. "Where the skills of daily living in the community were grossly deficient, it seemed pretentious to place major stress on vocational training" (PCMR, 1972).

- Second, as public education authorities expanded services to children labeled trainable, more and more parents kept their children at home rather than institutionalize them. Then, at age 17 or 18, these young adults left school. This created a crisis for families who were then without a day program for their children. As a result, the demand for institutionalization increased for young adults between the ages of 20 and 24, as did the demand for day programs.

The Start of Activity Centers

Workshops were hard pressed to support this new population.

In response to these pressures, the first activity center started in 1952 in Pennsylvania. Several more opened in the 1950s, including the Occupation Day Center of the NY ARC. By 1964, 94 centers were established by ARCs. After 1964, the growth of activity centers really took off.

Also during the 1950s, many people living in institutions were also working. For instance, the Vineland State School in New Jersey started the first work-study program for people with mental retardation in this country in 1956. People were in school half the day and in jobs in the community for the other half of the day. Some of the first people to leave institutions did so because they had jobs in the community. Ironically, other people left the institution to live in the community but returned to the institution to work.

Photo courtesy

William Bronston M.D.

Institutional Peonage

The other type of work for people in institutions was in the institution itself. By and large, this was unpaid work. In the 1960s, this would become a major issue. In the 1970s, federal courts ruled that unpaid resident labor in institutions was unconstitutional under the Thirteenth Amendment which prohibits involuntary servitude (peonage).