The 1960s: Children with Disabilities Brought into the Education System.

Issues of Race and Poverty. The Continuum and Least Restrictive Environments.

The President's Panel on “Mental Retardation”* proposed a program for "National Action to Combat Mental Retardation*" in October 1962. The Panel called for greatly extending specialized education training in general schools and in separate, “special” schools, substantially increasing the supply of teachers with appropriate training, educational background and coordinating the total resources of the community.

The Panel noted that:

- The number of children with developmental disabilities enrolled in special educational classes has been doubled over the past decade. In spite of this record, we are not yet meeting our existing requirements, and more such facilities must be provided. Less than 25 percent of our children with developmental disabilities have access to special education… Over 25 percent of those coming out of special classes still cannot be placed [in rehabilitation programs].

- Between 1948 and 1958, the number of day and residential schools offering special education for children with developmental disabilities increased from 868 to 3,202, or about 270 percent. But the number of special classes in operation was still grossly inadequate.

- … practically no programs exist which aid the adolescent or young adult with developmental disabilities in his transition from school to work and community living.

- Every State now has special legislation and makes some contribution to the education of young people with developmental disabilities.

The Panel recommended that:

-

The U.S. Office of Education should exercise national leadership in the development of educational services for children with developmental disabilities.

-

Specialized educational services must be extended and improved to provide appropriate educational opportunities for all children with developmental disabilities.

-

The States, communities and private foundations should undertake an extensive expansion of manpower training programs.

As a result, The Mental Retardation* Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 included provisions for training personnel, and research and demonstration projects in special education.

The Federal Government Plays a Makor Role

In 1965, the federal government began to play a major role in funding public education. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (P. L. 89-10) provided the first federal support for education. In 1966, the Act was amended (P. L. 89-750), and the Bureau for Education of the Handicapped* was established in the United States Office of Education to administer research, educational and training programs supported by the federal government.

The National Advisory Council on Disability was also established. The first federal grant program for the education of children with disabilities at the local level was created.

Federal funding for public education and for children with disabilities was important in its own right – more money for education. It also brought local education under federal civil rights protections. This became increasingly important in the 1970s.

The changes in the 1960s were basically structural. They put the mechanisms in place that could have an impact over the long term. In the short term, the President's Committee continued to recognize that there was a long road ahead. In 1967, the PCMR reported that half of the nation's 25,000 school districts offer no classes for pupils having special learning problems and needs.

A Range of Special Education Placements

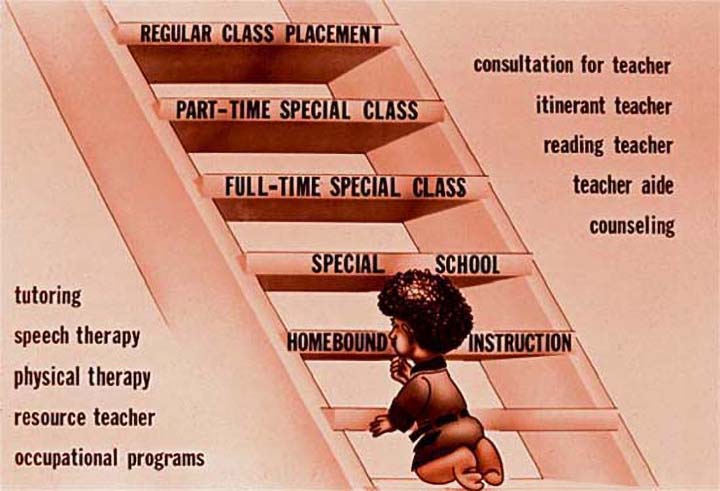

Developments in the early 1960s not only focused on the integration of students with disabilities into the public system. Leaders in the field of special education also advocated for the development of a range of special education placements so that at least some students would be integrated into public schools and classrooms.

The early 1960s also saw the introduction of a continuum of placements ranging from least restrictive to most restrictive was introduced (Reynolds, 1962).

In 1970, the continuum (placements along straight line) was described as a cascade (an inverted pyramid) (Deno, 1970). In the cascade, the least restrictive setting was at the top and broadest part of the pyramid indicating more students would be placed in the least restrictive environments.

The most restrictive settings were at the bottom and narrowest point of the pyramid, indicating the fewest students would be placed there. The principle of least restrictive environment was included in court rulings in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The number of stops on the continuum or shelves on the cascade varied, but the basic placements included the following:

- Full time placement in a general education classroom

- Full time placement in a general education classroom with special education consultation

- Full time placement in a general education classroom with special education tutoring

- Full time placement in a general education classroom with use of a resource room.

- Part time placement in a general education classroom and part time placement in a special class.

- Full time placement in a special class

- Part time placement in a special day school with part time placement in a general education classroom

- Full time placement in a separate, special day school

- Full time placement in a separate residential school (historically, the oldest plan since 1848)

- Hospital instruction

- Homebound instruction (including instruction for those excluded from school because no program is available to meet their needs. Children may be excluded because of behavior disorders that the school is unable to "control" but increasingly "exclusion is becoming more of an emergency, rather than a permanent, measure.")

Photo of graphic courtesy William Bronston, M.D

Special Education Becomes a Focus in War on Poverty

In the late 1960s, special education became a focus within the overall War on Poverty. The issue of poverty and mental retardation* received growing attention. Controversy grew about the traditional classification and placement practices.

The President's Committee and the Bureau of Education for the Handicapped* sponsored a 1969 conference titled "The Six-Hour Retarded* Child".

We now have what may be called a 6-hour retarded* child – disabled from 9 to 3, five days a week, solely on the basis of an IQ score, without regard to his adaptive behavior, which may be exceptionally adaptive to the situation and community in which he lives.

The concern focused on the mass migration of large numbers of low income families from minority groups to large cities.

A large number of these children score low enough on individual tests of intelligence to be classified as "mentally retarded*." They are sometimes called "functionally retarded*" to distinguish them from those who, presumably, would have been "retarded*" regardless of environment. The latter are sometimes called "organically retarded*" even when there is no evidence of "organic deficit*."

The production of so many "functionally retarded*" children by our society raises disturbing questions: Do we need more special education that is designed for the "retarded?" Do we need more of the same kind of education these children have been getting in the general classroom? What is the role of the schools in a society beset by racism, poverty, alienation, and unrest?

The conference's recommendations included some of the earliest uses of the terms "inclusive" and "zero reject," and reference to "nondiscriminatory evaluation," "individualized instruction," and "strength based planning" which would come to play increasingly important roles over the decades.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D

RECOMMENDATION: Hold the school accountable for providing quality education for all children.

ACTION: Public school systems should move toward becoming an all-inclusive (zero-reject) educational system.

RECOMMENDATION: Re-examine present system of intelligence testing and classification.

ACTION: Limit designation of "mentally retarded*" to those who do not show a significant increase in either intellectual or adaptive behavior normal for age in spite of various therapeutic attempts at correction of the program (e.g. no "final diagnosis" until after remediation has been applied)… Assess child's strengths so that appropriate planning and curriculum development can be provided, and instruction focused on strengths rather than weaknesses.

RECOMMENDATION: Restructure education of teachers, administrators, counselors.

ACTION: All teacher-training institutions should continue to seek new models for preparing professional teachers who can individualize instruction and handle diversity… Emphasize communication between general educators and special educators.

The conference also recommended a focus on early childhood stimulation, and education and evaluation as part of the continuum of public education. This recommendation was consistent with the President's Panel recommendations back in 1962. It helped build momentum for federal funding to early childhood intervention programs and the inclusion of younger children in education legislation.

The Exceptional* Child

Produced for the Educational Television and Radio Center by Syracuse University, 1969

"While preparing the Department of Special Education at Millersville University in Millersville, PA for a move into the new School of Education building I discovered a trunk with a set of film cans. The dusty military style footlocker contained 16mm films dating back to the founding of the department in 1958. I have been requiring teacher candidates in a foundations course to complete the MN Governor's Council on Developmental Disabilities online course Partners In Time and decided to contact the council in order to share these historic films. Most of the films originated in Syracuse in the 1950s and 1960s. One film, A Different Approach, originated in California in the 1980s. The films have significant historic value as we attempt to be coherent regarding services and supports being offered and designed today. The language, which may be harsh today, is a reminder of what was and a caution of what is. It is my hope that Individual and systemic consciousness, which currently manifests in a low awareness regarding the reality and dynamics of societal devaluation and deviancy-making is in some small way improved. Viewing the historic context may shine light on the present day impacts of special education and human services and offer guidance for today's professionals, college students, families, and people with disabilities."

| Mentally Deficient | The Blind | Speech Handicapped, Physical Disabilities |

| Mentally Handicapped | The Crippled Child | Stuttering |

| Partially Sighted | Cerebral Palsy | The Community and the Exceptional Child |

The Issues Reach the Courts

The relationships among poverty, race, standardized test and mental retardation* also made their way into the courts in the late 1960s.

Hobson v Hansen (1968) ruled that the Washington D.C. public school system's educational placement decisions were illegal. Children were being placed in educational programs on the basis of standardized tests that discriminated against certain minority and income groups. The Arc US noted that as a result, many children were "misclassified and placed in special education classes." The concern was that typical children were being placed in special education classes, leaving little room for children who "really needed the special instruction."

Diane v State Board of Education (1970) focused on the issue of Mexican-American children being placed in California's special classes for "mildly retarded* children." The class action suit ended in an agreement which said, among other things, that intelligence testing had to be in the student's primary language and that the state would undertake the development of more appropriate tests."

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Disproportionate Classification of Minority Students in Special Education

In 2002, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights echoed the issues of the 1960s:

The IDEA amendments of 1997 required that states report the number of students with disabilities served by race/ethnicity. Recent research commissioned by the Harvard University Civil Rights Project and another study by the National Academy of Sciences determined that students of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds are more likely to be placed in special education classes than their white peers. National statistics compiled by the Department of Education outline the disparities. For the 2001–2002 school year:

- Black (non-Hispanic) students account for 14.8 percent of the general population of students, but make up nearly 20 percent of the special education population.

- Black students' representation in the developmental disabilities category is more than twice their national population estimates, and their representation in the developmental delay and emotional disturbance categories is nearly two-thirds higher.

- Asian American/Pacific Islanders represent 3.8 percent of the general student population, but make up less than 2 percent of the population receiving special education services.

- American Indian students are also slightly overrepresented in special education in almost every disability category.

The Harvard Civil Rights Project found that in 1997 African American children were almost three times more likely to be labeled "mentally retarded*". They also found that students with disabilities in urban areas, in which minority students predominate, are more likely to be placed in segregated settings and less likely to have access to challenging curricula.