The 1970s: The Readiness Model

Demonstrating Another Way and a Third Stream, Supported Employment

In the 1970s, strong anti-discrimination legislation paved the way for change. While the sheltered options from the 1960s continued to grow, new approaches began to emerge which would open up more options for people with severe disabilities.

- Day activity centers gained increasing acceptance.

- The concepts of least restrictive environment and "getting ready" for the next less restrictive environment became more important.

- New approaches to training and support on the job emerged, especially for people with severe disabilities.

- Unpaid work in institutions was successfully challenged.

"It All Began With…"

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

In the 1970s, the day activity center increased in acceptance.

A 1972 study by the President's Committee on Mental Retardation noted that "the deficiencies which were identified in the first [1964] study – such as inadequate staff qualifications and evaluation procedures – have now been corrected or remedied in most areas." The PCMR recommended additional tax support for activity centers and that programs for 14 to 21 year olds should be supported fully by boards of public instruction.

The PCMR thought activity centers had important roles in supporting people who had moved from institutions, and allowing sheltered workshops and rehabilitation centers to offer personal grooming and social programs.

Workshops and rehabilitation centers sponsored programs that helped individuals get ready either for employment or sheltered workshop programs. Activity programs had also become "the hub of all regional operations in several places in the country."

The Day Activity Center was the first step along the vocational service continuum. A 1979 study by the U.S. Department of Labor, and the California Department of Finance established that people had a long wait to move to the next "higher level program."

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

| Program | Average wait to move to the next highest level | % of clients moving to the higher level during a year |

|---|---|---|

| Day Activity Center | 37 Years | 2.7% |

| Work Activity Center / Sheltered Workshop | 10 Years | 7.4% moved to competitive jobs 3% moved to a regular program center |

| Regular Program Center | 9 Years | 11.3% |

| Competitive Job |

In 2001, the General Accounting Office estimated that only about 5% of the workers in work activity centers left to enter integrated employment settings. They may or may not have received minimum wage or better in those settings.

In 1973, and 1974, the practice of unpaid work in institutions was successfully challenged in the courts. In three separate court cases in Washington, D.C., Iowa and Maine, the courts ruled that unpaid resident labor in institutions is unconstitutional under the Thirteenth Amendment which prohibits involuntary servitude (peonage).

The President's Committee made note of the irony that people who were working in institutions were somehow seen as incapable of working in the community. "One of the principal arguments that remains unanswered is why anyone capable of working in an institution cannot be gainfully employed, at least in a sheltered setting." For instance, at least two states, New York and New Jersey, employed significant numbers of former residents at institutions while providing them with transitional living arrangements elsewhere. One of the unanticipated results of the court cases was that many residents were left without work and without individualized treatment programs with vocational training. In other words, they were made idle and not always moved into the community.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

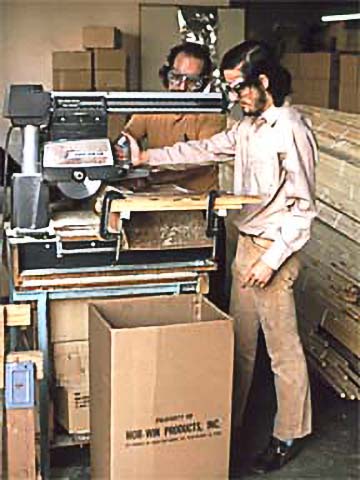

At the same time, employers continued to gain experience with the employment contributions of people with less severe disabilities. The federal initiative in the 1960s opened many doors. The ARC National On-the-Job Training Project also began in 1964 but really produced results in the 1970s.

From 1969 to 1979, it placed 25,000 individuals in competitive employment. Most of the workers were retained by employers who were willing to provide training. In 1987 The Arc's On-The-Job Training Project changed its name to National Employment and Training Program (NETP) in order to reflect its expanded scope. In 1987, the NETP encompassed such activities as supported employment, professional and volunteer training, job development and placement, and more.

For most people with developmental disabilities in the 1970s, the two streams – day activity centers/sheltered workshops and competitive employment – continued to be the major options. Training-on-the-job opened the doors for some who might not have worked their way along the continuum into community jobs.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

People with severe disabilities, however, were still seen as benefiting only from day activity centers. They were not likely to move along the continuum.

A third stream, however, began to emerge in the 1970s that would offer, over time, a wealth of employment opportunities for people with severe disabilities. This third stream combined a support technology for people with severe disabilities and a value base that insisted that they have access to community opportunities.

The value base for real work for real wages in integrated settings began to evolve in the 1970s through the work of visionaries such as Marc Gold, Lou Brown, Tom Bellamy, and Paul Wehman. Research and demonstration work at university centers (especially, Oregon, Wisconsin and Virginia) supported people with severe disabilities to do real work and gain competitive employment.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

The idea of supported employment and the term, "job coach" emerged from this work. The demonstration work focused on supporting adults in both employment and educational programs that looked forward to employment for people with severe disabilities.

The principle of normalization began to be applied to the world of work in earnest. Lou Brown's definition of real work is a prime example – work that if done by a person without disabilities would earn a wage.

The concept of "natural proportions" is another – that people with disabilities are present in work environments in the same proportion as their presence in the general population. Brown's work in the Madison school system underscored the impact of effective support in the school years for more successful outcomes for adults in employment.

Marc Gold's values and training programs opened the eyes of many to the employment possibilities for people with severe disabilities. During the late 1960s, Marc Gold was a special education teacher in East Los Angeles. He began to formulate a conceptual framework of instruction based on a few fundamental beliefs:

- His students with severe disabilities had much more potential than anyone realized.

- All people with disabilities should have the opportunity to live their lives much like everyone else.

- Everyone can learn if we can figure out how to teach them.

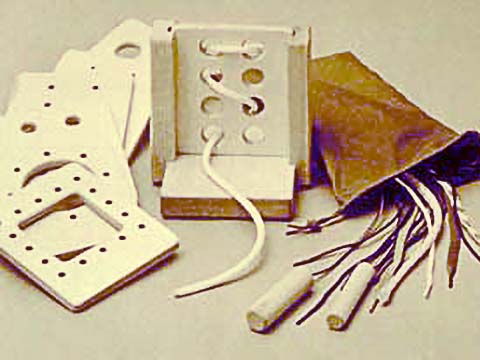

In the 1970s, Gold developed and presented three day workshops across North America on this new systematic training approach he called "Try Another Way." This system provided an organizational framework, instructional strategies, and a value base useful for teaching persons with even the most severe disabilities to perform sophisticated tasks or competencies.

Marc Gold

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

At the time, people who were merely willing to have people with the most severe disabilities in their programs were considered innovative. Gold felt that this simply was not good enough. He felt that all persons could grow and have dignity and control of their lives.

Gold was one of the first to question the widespread use of behavior modification strategies for training purposes. He felt that an emphasis on reinforcers, even positive ones, led to an unbalancing of the relationship so necessary for respect between trainers and learners.

The concept of individualized, negotiated jobs developed out of Gold's strategy of breaking down a complete job into teachable tasks that match the skills, needs and preferences of people with disabilities, then forming the tasks in a newly defined job.

All of this work took place in the context of significant changes in legislation.

Marc Gold

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-112, Section 504) is often called the first civil rights act for people with disabilities (the second being the Americans with Disabilities Act). It authorized over $1 billion for training and placement of people with mental and physical disabilities into employment. It also provided the first focus on rehabilitation services for people with severe disabilities. Section 504 prohibited discrimination based on disability by any agency (including employers) receiving federal funds.

Karen Flippo recalls, however, that the impact of the anti-discrimination provisions was delayed.

In 1977… on my first day of work, I walked a couple of blocks to the Federal Building in San Francisco. Outside, protesters were calling for the promulgation of regulations for Section 504(d) of the Rehabilitation Act. The few words carried in the regulations symbolized the power that drove the disability rights movement for many years, "no otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall, solely by reason of his handicap, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving financial assistance."

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

In 1978, the Rehabilitation, Comprehensive Services, and Developmental Disabilities Amendments of 1978 (P.L. 95-602) broadened the scope of Section 504 to include the executive branch agencies of the federal government and the Postal Service.

Requirements common to federal agency Section 504 regulations included reasonable accommodation for employees with disabilities; program accessibility; effective communication with people who have hearing or vision disabilities; and accessible new construction and alterations. It also established new programs for people with disabilities, including independent living centers and pilot programs for employment.

While these were significant changes in legislation, it is important to remember that the Federal-State vocational rehabilitation program is an eligibility-based program, not an entitlement program.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

To receive vocational rehabilitation services, an individual must meet three eligibility criteria.

- First, the individual must have a disability that causes an impediment to employment.

- Second criterion is the presumption of employability.

- Third the individual requires vocational rehabilitation services in order to become employed.

Prior to a profound change in the legislation in 1992, state vocational rehabilitation agencies routinely presumed that individuals with severe disabilities were unemployable – they did not meet the second criterion. Congress determined in 1992 that the "employability" criterion was weeding out individuals with severe disabilities on the assumption that, in fact, they were too severe to be employable.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

So in 1992, Congress said State vocational rehabilitation agencies will assume that everybody who has a disability can work. In other words, State vocational rehabilitation agencies would have to prove the assumption wrong rather than simply assuming the person was ineligible.

"Solidarity Forever"

Civil Rights: "We're Going To Win This One"

The Fight for 504 Regulations – "We Won't Go Away"

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy Hank Bersani Ph.D

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy Hank Bersani Ph.D

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.