The 1960s: The Growth of a Highly Segregated System.

A Valuing Focus on Work, At Least For Some.

Three major developments dominated the 1960s:

- The President's Panel on Mental Retardation called for major attention to the employment of adults and the preparation of young people for employment.

- Major growth in the numbers of day activity centers and sheltered workshops across the country, and federal funding to aid in that expansion.

- Widespread experience with people with developmental disabilities working in real jobs for minimum wage or better, thus bolstering an analysis of the positive economic impact of employment.

Underlying these developments was a fundamental assumption – while the vast majority of people with developmental disabilities could work, many were too severely disabled to do so.

For "the mildly retarded", the career track was fairly straightforward – train for employment, preferably from an early age, then place the person on the job. For everybody else, long term placement in sheltered settings was the prognosis.

The President's Panel on Mental Retardation (PPMR) did bring public attention to the important contribution that people labeled mentally retarded could bring to the community.

The preparation of the mentally retarded for a useful role in society and industry must receive more attention. In the past 5 years the number of mentally retarded rehabilitated through State vocational agencies has more than tripled – going from 756 to 2,500 – but in terms of potential, it is little more than a gesture.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

It is important to remember that in 1962 "rehabilitated" could, and often did, mean placement in a sheltered workshop. It was not until the year 2000 that extended employment (that is, work activity center or sheltered workshop placements) would not be considered an appropriate outcome of vocational rehabilitation. Nevertheless, the PPMR did make a strong case for people getting real jobs with regular employers.

The PPMR also recognized the economic implications of people getting real jobs and real incomes.

The economic value of vocational rehabilitation for the retarded is clearly demonstrable. A study of 1,578 mental retardates who were rehabilitated in 1958 estimated that their total annual earnings rose from $70,000 before rehabilitation to $2.5 million after rehabilitation.

The PPMR also recognized the economic implications of people getting real jobs and real incomes.

The economic value of vocational rehabilitation for the retarded is clearly demonstrable. A study of 1,578 mental retardates who were rehabilitated in 1958 estimated that their total annual earnings rose from $70,000 before rehabilitation to $2.5 million after rehabilitation.

The President's Panel recommended large scale investments in vocational rehabilitation services, and education programs to prepare people for work. The Panel's recommendations included:

- Increase state matching funds.

- Strengthen school counseling programs.

- Fully utilize the testing, employment counseling, and placement programs of the 1,900 employment service offices.

- Use and improve training programs.

The Panel suggested that appropriate vocational rehabilitation services be available prior to, during and after termination of formal education, including:

- Evaluation, counseling and job placement

- Joint school-work-experience programs operated cooperatively by schools and vocational rehabilitation agencies

- On-the-job training programs

- Employment training facilities

- Sheltered workshops for workers capable of productive work in a supervised, sheltered setting

- Vocational rehabilitation services in conjunction with residential institutions

- Counseling services to parents to provide them with an adequate understanding of the employment potentials of their children

- Coordination of vocational counseling with the entire school program

The recommendations from the President's Panel supported some major legislative action.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D

The Expansion of Sheltered Day Programs

The expansion of day activity centers and sheltered workshops was aided by the 1963 Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act (P.L. 88-164). The federal government provided financial aid for building community based facilities, including day facilities for people with developmental disabilities and people with mental illness.

The 1965 Vocational Rehabilitation Act Amendments (P.L. 89-333) required that vocational rehabilitation services be provided to people with severe disabilities. It allowed extended evaluation periods for persons with developmental disabilities and similar disabilities.

Day program expansion was particularly strong in terms of day activity centers. Between 1952 and 1964, ARCs developed only 94 day activity centers. In 1964, another 91 new programs were being planned, beginning a period of major expansion. Over 600 new centers were established between 1964 and 1972.

By 1972, Minnesota had the most activity centers (86) of any state, and according to the President's Committee on Mental Retardation (PCMR), had "taken the lead in not only having the most activity centers but also in the important area of establishing standards for the operation of these programs."

Reason for the Expansion of Programs

One of the major reasons for this expansion, according to the President's Committee, was that activity programs had very definitive roles in state-wide plans for the continuum of programs and services. In addition to preventing institutionalization, activity centers began to enhance public school special education programs for trainable adolescents and young adults by cooperative-joint programming.

In some places the schools had people with developmental disabilities for one-half of the day and the activity center had them for the remaining part. Activity programs have also promoted the growth and development of public schools classes for trainable students between the ages of 17-21 years

The growth of segregated programs was truly remarkable. Paul Wehman estimates that there were well over 1,000,000 persons in 5,000 segregated day programs in the United States alone during the 1960s.

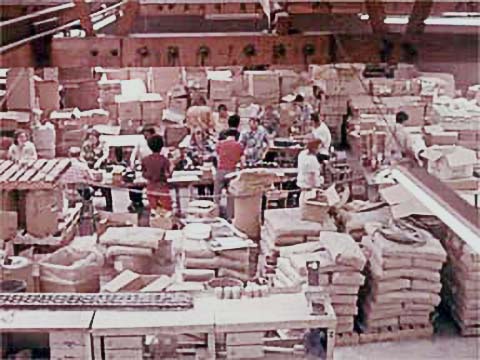

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Building on Experience

At the same time, there was growing experience with the participation and contributions of people with developmental disabilities in the real world of work. The Federal Government provided significant leadership in hiring people with developmental disabilities.

In 1964, the first full year of the program, 361 placements were made. By mid-1967, the cumulative number of placements was 3,241 and 79% of all appointees were still on duty. Only 7% of the placements were ended because of poor performance or social adjustment. Most of the placements were in jobs titled laborer, clerk, messenger, substitute mail handler, laundry worker, and food service worker.

Nevertheless, the placements spanned 64 different job titles in 38 Federal agencies in 50 states. Many of the jobs (25%) were in the Washington, D.C. area. By the end of the ten year program, the federal government employed 7,500 people labeled mentally retarded. The federal program was complemented by the National ARC training-on-the-job project which had its greatest impact in the 1970s.

Photos courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Amending Section 14

In 1966, Section 14 was amended to define "special minimum wage" as not less than 50% of the national minimum wage and commensurate with the wage paid to workers without disabilities in industry in the vicinity for essentially the same type, quality and quantity of work.

Agencies providing vocational rehabilitation services for evaluation or training programs for people with multiple disabilities and work activity centers, however, could get certificates which allowed them to pay below the 50% minimum.

In 1967, the PCMR reported that an estimated 2 million people with developmental disabilities were capable of learning to support themselves and needed job training and placement services. Even at minimum wage, these individuals were said to have a potential annual earning capacity of $6 billion.

"Even at minimum wage" was, however, a fairly risky assumption in the late 1960s. Back in 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act created a federally-mandated minimum wage, but it also created an exemption for "handicapped workers." Section 14(c) allowed employers with special certificates to pay below the federal minimum wage.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Payment for Work in Institutions

These provisions allowed employers to negotiate lower wages for potential workers with disabilities. In some cases, this might mean a job placement for someone who could not produce competitively. In other cases, it might mean productive workers with disabilities were not hired unless they (or the agency) agreed to apply for a certificate.

The far more usual use of the certificates, however, was in sheltered environments. By 2001, only 9% of certificates were in community businesses.

People in institutions in the 1960s were also working, often in the institutions where they lived, and often for no wage whatever. In 1968, the NARC adopted a statement about pay for work in institutions. "Residents performing jobs related to maintaining and operating the residential facility should receive pay [and working conditions] commensurate with their ability for work performed. Working for the benefit of the institution should not be confused with training programs designed to benefit the resident."

The President's Committee estimated that by 1970 the value of unpaid resident labor in "facilities for mentally retarded persons and by mentally retarded residents of public mental institutions" was $1.25 million. The work included housekeeping, laundry, repair work and care of other residents.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.