Social Reforms

Samual Gridley Howe

Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe (1801-1870), an American physician, educator for the blind, and abolitionist, was deeply concerned about many social causes and advocated for the improvement of publicly funded schools, prison reform, humane treatment for people with mental illness, oral communication and lipreading for people who are deaf, as well as anti slavery efforts.

Dr. Howe completed his medical education at Harvard Medical College, graduated in 1824, and left for Greece where he served as a surgeon in the Greek War of Independence. While abroad, he visited Dr. Guggenbuhl's Abendberg school and heard of Seguin's work in France. When he returned to the United States in 1831, he began teaching a few blind children at his father's house in Boston and gradually developed what became known as the Perkins School for the Blind.

In 1848, Dr. Howe established The Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth, an experimental boarding school in South Boston for youth with intellectual disabilities. Both Seguin and Howe firmly believed in the importance of family and community and wanted their schools to prepare children with disabilities to live together with all of society.

At this time, most social reformers in America believed "idiots" could not be taught. Many believed phrenology , "the practice of studying the shape of the skull to determine human characteristics and functions," offered the only hope of understanding disabilities.

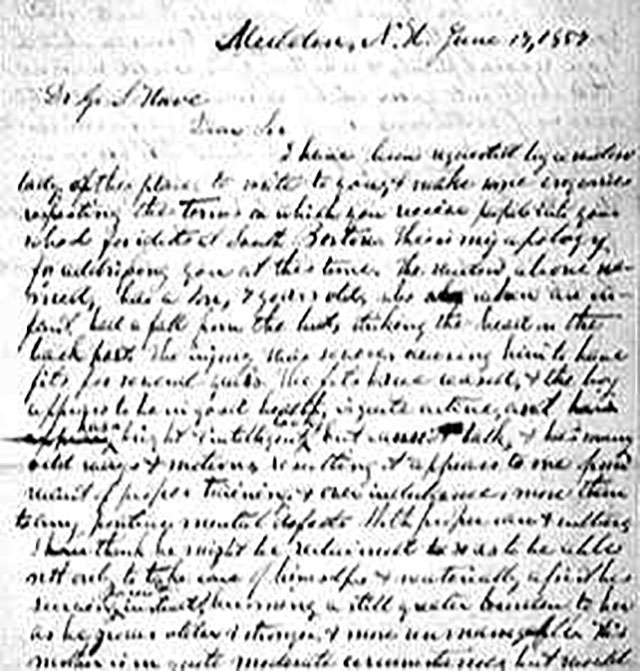

Audio: Letter on behalf of a patient

Samuel Gridley Howe

Dear Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe,

I left an application at your office in Bromfield Street yesterday on behalf of James [Doe] who desires to have his son admitted into the Institution for Feeble-minded Youth. James is an industrious man who has been employed as a gardener by my father and myself, more or less, for the last four years. His boy has grown to be exceedingly troublesome, escaping from home as often as possible and causing his parents much anxiety. Of late they have felt obliged to confine him in the cellar during the father's enforced daily absence. I beg you will give the case your kind consideration, assured that it is a worthy one and deserving prompt treatment.

Very respectfully yours,

William [Doe] July 7, 1841

Hervey B. Wilbur

A private school similar to Howe's was also started in New York in 1848 under the direction of Hervey B. Wilbur . Wilbur started the school in his own home and instructed his students according to Seguin's teaching methods. Soon, a number of boarding schools for children with disabilities opened on the East Coast.

Training schools were considered an educational success, offering hope to many families with children with disabilities. A school for "feeble-minded youth" opened in Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1852, followed by another in Albany, New York in 1855, and one in Columbus, Ohio in 1857. School superintendents had a strong educational focus and followed Seguin's teaching methods that included physical training for students to improve their motor and sensory skills, basic academic training, and instruction in social and self-help skills.

Early School

During this time, the U.S. Government made its first attempt to determine the number of persons with intellectual disabilties. Although these efforts may have been flawed by confusing mental illness with intellectual disability, there was a reported increase in the number of persons with disabilities during the 19th century:

Census Results for Mental Retardation

| Year | Number of persons | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 15,706 | .07% |

| 1860 | 18,865 | .06% |

| 1870 | 24,527 | .06% |

| 1880 | 76,895 | .15% |

| 1890 | 95,571 | .15% |

Some people, believing the increase was due to the large number of "defective immigrants", argued for the construction of more and larger institutions. At the same time, however, there was a significant increase in the overall population.

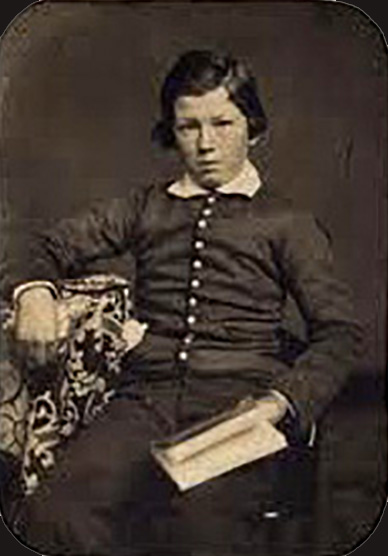

Grubb, an inmate at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children, ca. 1857

Hope in Proper Training

During this historical period, there was an underlying belief that, through proper education and training, and humanitarian means, many persons with disabilities could be educated to return to the community and lead productive lives. We could "make the deviant undeviant," changing them to fit better in the world.

Optimism for the early 'training schools', a growing awareness of the number of persons with disabilities, and the advocacy of social reformers including Dorothea Dix, contributed to the building of more and more institutions.

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century dramatically changed patterns of human settlement, labor, and family life throughout Europe, the United States, and much of the world. Major changes in transportation, manufacturing, and communications ,coupled with the rapid expansion of cities and significant population increases, resulted in people "working for slave wages and living in squalid conditions. Children represented a large portion of the workforce, performing grueling work for twelve to sixteen hours per day. Pauper children were often contracted to factory owners for cheap labor." To do away with "imbecile" children, parish authorities often bargained with factory owners to take one of these children with every 20 other children.

Boys' classroom at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children, 1866