Fear and Suspicion

Individuals with disabilities became scapegoats during this period. Shifting the focus of the earlier theme of "protecting the deviant" from society, this era became less concerned with persons with disabilities, and more suspicious of people viewed as "different."

The number of individuals in public institutions continued to rise, averaging approximately 250 persons per institution in 1890 and over 500 per institution by 1905. In a relatively short time, practices shifted from compassionate education and training to segregation.

In 1900, about 10 private institutions housed individuals with disabilities. By 1923, that number had increased to 80 and they came to be known as schools, farms, hospitals, institutes, and academies.

Private institutions

Worsening Conditions

In 1894, Rome State Custodial Asylum for Unteachable Idiots opened in Rome, New York. This institution provided basic care for persons with disabilities of all ages and both sexes, especially those individuals labeled as "low grade" or delinquent, and were often judged to be the result of the moral failure of their parents.

Overcrowding of institutions worsened as the 20th century proceeded. People could spend their entire day in one room and often slept on the floor.

Industrial training at the Rome State School in New York, ca. 1920

Rise of Eugenics

Changes in the treatment of persons with disabilities did not occur in isolation. Throughout the United States, great changes were occurring as the rural landscape was being replaced with the industrial city. The following events contributed to how society perceived individuals with disabilities:

- Around 1890, a large number of people from Eastern Europe immigrated to the United States. People with strange names, and different languages and customs settled on the east coast. These immigrants were willing to work hard for low wages, and posed a major economic threat. Anyone who looked or acted differently was feared.

- In 1893, Walter E. Fernald, president of the American Association on Mental Deficiency, stated that institutional care was economical and conservative, not just charitable. According to Fernald, "each hundred dollars invested [in institutions] now saves a thousand [dollars] in the next generation." This served to financially justify the building of more institutions. In the late 1800s, the annual cost per resident in a state institution was between $150 and $200.

- By 1900, one out of every seven Americans was foreign-born.

- In 1913 the United States Public Health Service administered the newly invented Binet IQ test to immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. Professional researchers recorded that "79% of the Italians, 80% of the Hungarians, 83% of the Jews, and 87% of the Russians are feeble-minded." The validity of the test was not challenged and test results served to reinforce negative images of immigrants.

- Around the turn of the century, a xenophobic hysteria focused on racial minorities as well as persons with disabilities. Government-supported actions that excluded and segregated African Americans and persons with disabilities evoked, reinforced, and legitimized public and private prejudices.

- In 1905 in France, Dr. Alfred Binet and Dr. Theodore Simon developed an intelligence scale of 30 items that was intended to distinguish between school-aged children of subnormal and normal intelligence. Dr. Binet established three rules for the use of this scale: Rule 1: The scores do not define anything innate or permanent. Rule 2: The scale is a rough guide for identifying and helping learning-disabled children. Rule 3: Low scores don't mean a child is innately incapable.

- In 1917, Dr. Goddard and his associates administered a version of the Binet test to 1.75 million army recruits. The results found that 40% of the white male population was feebleminded.

- In 1924, Congress passed the Immigration Restriction Act.

- The late 19th and first quarter of the 20th centuries saw the rise and consequences of the Eugenics Movement, that supported and promoted "the science of the improvement of the human race by better breeding". So-called "feeblemindedness" was thought to be hereditary, and was eventually blamed for most of society's burdens. Many proponents of eugenics were doctors who advocated for the sterilization of persons with disabilities based on a belief that they would eventually ruin the human species if they reproduced.

- Social Darwinism, a theory about the biological evolution of species, was developed and advanced by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809 - 1882). Darwin's theory was grounded in a process of natural selection that also governed the affairs of society and social evolution.

- Herman Spencer (1820 - 1903), an English philosopher and anthropologist, built on and promoted Darwin's widely accepted theory. Spencer was optimistic about the improvement of human beings and believed that human relationships could be reduced to scientific principles. Darwin's observations on the natural order of plants and animals reinforced Spencer's belief that the social order was governed by the "survival of the fittest." His belief helped to justify forced sterilizations, marriage restrictions, and the warehousing of individuals with disabilities in institutions.

- Compulsory public school attendance laws were enacted during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As public school attendance increased, teachers noticed more pupils who were "slow and backward." Teachers began to call for persons with special training and for special classes to take care of these students.

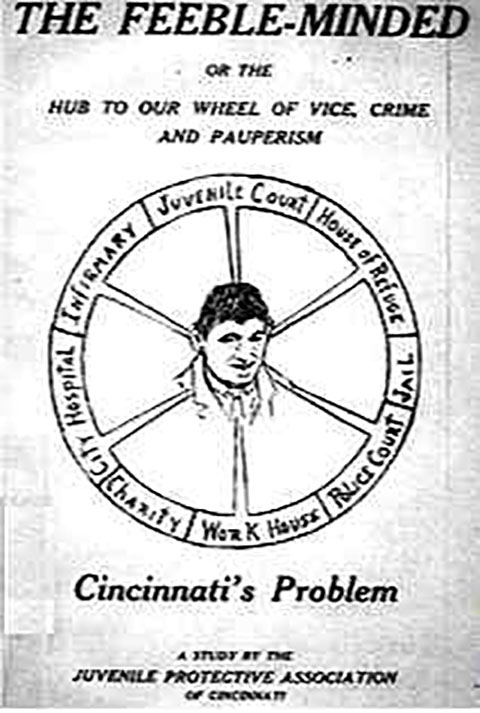

Menace to Society

During this period, fences that had served to protect the residents of the institutions from the dangers of society now served to isolate them in order to protect society from the "menace of feeblemindedness."

An increasing amount of misinformation about persons with disabilities that they were dangerous, immoral, capable of ruining the gene pool promoted this "menace" theme. Institution superintendents who had previously argued for the humane care and protection of persons with disabilities, were now convinced that individuals with disabilities were a danger to their communities.

Feeblemindedness had to be prevented; individuals had to be controlled.

The Moral Imbecile

"Moral imbecility," also referred to as juvenile insanity, moral insanity, physical epilepsy, and moral paranoia, was a broad concept that included everything from minor behavior problems to serious aggressiveness.

Persons placed in this category were also referred to as "defective delinquents." These labels implied an aptitude for misconduct, and the people who were given these labels were perceived as potential causes of the social problems of this time.

In 1910, Dr.Henry Goddard, using an adaptation of the Binet IQ test, developed a category of mental retardation he called "moron." This term replaced the terms "moral imbecile" and "backward," and added the notion of heredity.

During this period, a popular belief was that mental retardation and mental illness were completely genetic, and caused most, if not all, social ills such as poverty, drunkenness, prostitution, crime, and violence. In response to this belief, individuals labeled mentally disabled or mentally ill, were segregated or sterilized to prevent them from reproducing and destroying the gene pool.

Pictures of people who committed arson, murder, or other acts of violence were often drawn in newspapers to suggest the presence of mental retardation. As late as 1920, the Public Health Service combined "criminals, defectives, and delinquents" into a single category.

By the 1920s, the "menace" theme peaked in our country as Dr. Henry Goddard, a psychologist at the Vineland Training School,explored the role of the environment versus the role of heredity in the lives of persons with disabilities.

The Kallikak Family

Dr. Goddard and his research assistants decided to explore the family history of a woman they named Deborah Kallikak ("Kallikak" being a fictitious name taken from the Greek words for "good" and "bad"), who lived in their institution.

They claimed they discovered that Deborah's great-great-great-grandfather was a revolutionary war soldier named Martin Kallikak. Apparently, Martin had relations with a "feeble-minded" bar maid.

Martin later returned to Philadelphia, where he married a woman of the upper class and raised a family. The bar maid, meanwhile, gave birth to Martin's child and not-so-feeblemindedly named him Martin Kallikak Jr. As an adult, the fictitious Martin, Jr. was known as "Old Horror." Dr. Goddard reported that 143 of this man's descendants were feebleminded, and included prostitutes, alcoholics, people with epilepsy, and criminals.

Dr. Goddard traced the lineage of Martin Kallikak's family with his wife and found only successful, upstanding individuals of normal or better intelligence. Dr. Goddard's conclusion, which he published in a widely-read book entitled The Kallikak Family, was that mental retardation is hereditary and the root cause of many social problems.

As Goddard stated in his book, "There are Kallikak families all around us. They are multiplying at twice the rate of the general population. and not until we recognize this fact, and work on this basis, will we begin to solve [our] social problems." His story was widely read and affirmed what people had been led to believe and wanted to believe: a group of people in our midst who will ruin the genetic strain if allowed to do so.

Goddard's book was eventually repudiated when his underlying research was exposed as scientifically invalid.

Deborah Kallikak

Parole and Sterilization

The 'moral menace' threat also affected persons with mild or moderate disabilities who lived in the community as they were now labeled morons and viewed with suspicion. As a result, many of these individuals were placed in already crowded institutions with long waiting lists. In order to make room, superintendents, who continued to promote the moral menace idea and that persons with disabilities could potentially ruin the human species, began paroling higher - functioning inmates but only when they were sterilized before being released.

The first sterilization procedure performed on inmates, around the turn of the century, was castration. This procedure was usually done on "low-grade imbeciles" who displayed "obscene habits" in the institution. Vasectomies were performed on men and tubal ligations on women.

in 1927, Buck v. Bell, a sterilization case concerning Carrie Buck who was labeled "feeble-minded", reached the United States Supreme Court. A family tree showed that Carrie and her daughter, Vivian, was the third generation of people with limited intelligence. On that basis, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes declared that "three generations of imbeciles are enough!" and approved the sterilization procedure. Later studies, however, proved that Carrie and Vivian were not feeble-minded and her family tree had been concocted. However, sterilizations were still permitted because of the belief that mental retardation was hereditary.

The belief that mental retardation was hereditary continued to prevail, and while forced sterilizations were still performed at many institutions, the eugenics movement lost its backing. An increasing knowledge and better understanding of the causes of disabilities cast doubt on Goddard's conclusions. The eugenics movement, however, resulted in tens of thousands of forced sterilizations due to misguided fears about people with disabilities and as a method of social control.

Beginning of Special Education

Special education emerged during this period. Public school teachers became increasingly aware of the number of students with learning disabilities, labeled "backward" or "feebleminded," and called for special classes and the teachers who could educate them. In 1896, Rhode Island opened the first special education class in the United States. By 1923, almost 34,000 students were in special education classes.

In search of training techniques for these children, the schools turned to the institutions. Some institutions expanded their facilities to incorporate "special" schools. Other institutions offered classes to school teachers on training techniques.

The Almosts

The 'menace' theme remained prevalent during the early years of special education. While many teachers believed in its benefits, Dr. Goddard and other professionals claimed that mental disability was hereditary, a social problem that could not be improved with education.

Professional publications perpetuated this message. The Almosts: A Study of the Feeble-Minded, a popular textbook, referred to people with mental disabilities as almost human. As a result, families with a child labeled "feebleminded were stigmatized as morally bad or genetically flawed, and advised to institutionalize them or keep them out of sight. In this atmosphere, families who had a child labeled "feebleminded" were stigmatized as morally bad or genetically flawed. The message given to families was to institutionalize their children or keep them out of sight."