Community Living Alternatives Develop

The Waiver shaped a range of services over time, illustrating how community living alternatives developed alongside on-going ICFs/MR services.

Home Based Supports. Services and supports are provided for an individual in his/her natural home. The type of support is tailored to the individual's need. Examples of this service include:

Therapy and Respite. An individual may also receive "day time" services, including Employment supports. Funding for these services is through the In-Home Waiver.

Family/Companion Living. (Also known as Life Sharing). An individual receives services and supports as an integral part of a caring family, though not with natural parents. The family home is licensed, the family receives training and the agency provides supports to the individual and the family through the program specialist. Waiver funding is used to support individuals in Family / Companion Living.

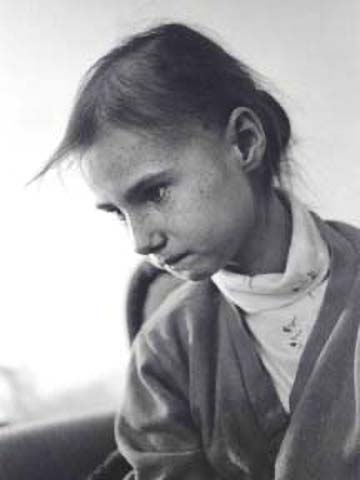

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Supportive Living Arrangements. An individual receives less than 30 hours per week of staff supports. The individual may live in his/her own apartment or family house, either alone or with housemates. Whenever possible, waiver funding is used for these supports (such as meal planning, money management, etc.).

Community Homes (CLAs). An individual receives supports and services in a house or apartment with up to 24 hour/7 day per week staffing. The CLA is the individual's home for as long as he/she desires. Philadelphia provides funding for over 550 Community Homes. There are 30 agencies under contract with the city to provide the supports and services tailored to the needs of each individual residing in a CLA. These homes are licensed by the State Department of Public Welfare. Usually, three people live in each home; but there are homes for as few as one person and as many as six. The larger homes are typically homes that opened in the 1970's or early 80's. All new development for Community Homes is for three or fewer people. Over 78% of these services are supported through waiver funding.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Intermediate Care

Intermediate Care Facilities for Persons with Mental Retardation (ICFs/MR) provide services and supports for people who can benefit from active treatment.

There are 31 small (nine or fewer people) ICFs/MR and three large (84 to 147 people) in the city. The eight agencies providing this service are under contract with the State Department of Public Welfare and must comply with federal regulations governing the actual provision of services.

The city is responsible for all referrals to ICFs/MR and for providing oversight.

Funding for ICFs/MR encouraged states to invest in the transformation of state institutions into ICFs/MR. The HCB Waiver encouraged states to invest in community based services and supports.

By the end of the 1980s, the impact of the Waiver began to accumulate nationwide. Almost 44,000 people were participating in waiver programs, while over 144,000 were residents of ICFs/MR. In 1982, only three states had a waiver for people with developmental disabilities. By 1987, over 30 states had at least one waiver, and by 1992, 46 states were participating. By 1995, there were more people participating in waiver programs (over 166,000) than resident in ICFs/MR (134,384).

This was in spite of some of the significant restraints on the waivers – needs of the individual (level of support and being at risk of institutionalization) costs compared to institutions, limits on the size of the waiver programs, the pace of approvals.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

Ongoing Controversies

These changes in direction during the 1980s do not mean that the ongoing controversy of deinstitutionalization and community living were quieting.

Landesman and Butterfield (1986), for instance, summed up the controversy in words that echo from the 1960s:

As goals, normalization and deinstitutionalization are not terribly controversial. As means to achieving these goals, the current practices of deinstitutionalization and normalization are exceedingly controversial.

At the heart of the debate are fundamental differences in beliefs and values about the extent to which the environment affects the functioning of those individuals with disabilities and what types of environments are best for whom.

In other words, the questions were still the same – who qualifies for living in the community, and for whom are institutions still necessary? Successful court cases and the direction of federal policy, however, began to shift the burden of proof to those who questioned deinstitutionalization.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

All People with Developmental Disabilities Can Live Successfully in the Community.

The leadership for community living for all people was clear – all people with developmental disabilities, including those with severe developmental, behavioral, and health impairments can live successfully in the community if appropriately supported.

According to Steve Taylor, there were ongoing and grave concerns about improving the quality of supports in the community, preventing the community from becoming like the institution, and how to promote relationships, choice and self-expression.

But for increasing numbers of people, and increasingly in public policy, the bedrock knowledge included the following:

- Institutions and other large, segregated living arrangements are unacceptable places to live.

- Any resources available in institutional settings can be made available in community settings.

Photo courtesy William Bronston, M.D.

The evidence and experience of people indicate that life in the community is better than life in institutions in terms of relationships, family contact, frequency and diversity of relationships, individual development, and leisure, recreational, and spiritual resources.

- All children with developmental disabilities can be supported in natural, adoptive or foster families.

- Both children and adults benefit from stable relationships with other people, including family members and community members without disabilities.

- People with developmental disabilities can and do make positive contributions to the life of the community.

The change in the nature of residential settings during the 1980s reflects a growing commitment to these statements.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

A Growing Commitment

There was also a growing commitment to supporting people to live in their own homes, rather than in residential services. In part, this meant designing ways to avoid people having to move when their support needs changed.

Often, the "continuum of service" idea, coupled with various functional assessment and adaptive behavior indexes, required people to "graduate to the next less restrictive environment".

An individual might leave an institution, move to a large group residence to receive training, then move to a smaller group home, then a semi-independent setting, and perhaps eventually to independent living. People were assessed in terms of their readiness for the next step along the continuum.

Court ordered processes such as the Pennhurst closure and developments supported by the HCBW enabled more and more people to start out in smaller and smaller settings with the support they required.

For people leaving Pennhurst, for instance, the more challenging their behaviors or other support needs, the less likely they were to live with other people with disabilities. Individuals received the support they needed in their own homes in the community.

When they required less support, they stayed where they were, and the support left. People only moved when they wanted to move.

Photo courtesy Ann Marsden

In an interview with Ed Skarnulis, Toni Lippert speaks about her views and vision of a service delivery system in Minnesota that incorporates the normalization principles of Wolf Wolfensberger; inclusive learning and living environments; and the beginnings of the concept of self advocacy.