An international authority on disability issues, Bengt Nirje of Sweden visited Minnesota state hospitals in 1967 before meeting with Governor Harold LeVander.

Nirje preached the "normalization principle," already successful in Scandinavia. This principle urged that people with developmental disabilities receive the same level of housing, schooling, and medical care provided for all other people.

Calling some Minnesota hospital conditions "horrible," "inhumane," and "impersonal," Nirje observed that he had witnessed "new means of degrading people" during his visits.

Swedish expert Bengt Nirje found Minnesota institutions "horrible" and "inhumane."

Arc continued to act as advocate for people with developmental disabilities, testifying before the Legislature that it was time to resolve the future of Minnesota's state hospitals once and for all.

At the hearings, witnesses outlined the need to reduce overcrowding. They also noted that current proposals to regionalize services neglected to discuss what happens to the residents currently living in Minnesota's state hospitals.

For decades, Arc was one of the state's

most vocal and effective advocates for people

with developmental disabilities.

In 1968, attorney Mel Heckt led a group of 11 judges, lawyers and law enforcement officials in drafting statutes protecting rights for people with developmental disabilities.

The Arc identified a legislative agenda that emphasized rights for people with developmental disabilities. The organization felt this emphasis was necessary before community services could be expanded.

Mel Heckt

An August 1964 study showed that half of the state's more than 6,350 residents were assigned jobs in institutions, raising the issue of "institutional peonage."

Institutional peonage is work, servitude or slavery in exchange for protection.

By law, a person with mental retardation could earn no more than $1 a month. Replacing institutionalized residents with civil service employees would require more than 900 additional positions at a cost of $2.4 million.

Residents of state institutions worked at a variety of jobs for a mere $1 a month, raising concerns about institutional peonage.

Keeping pace with Minnesota's accelerating efforts, federal programs also were expanding. In 1968, a federally-funded planning effort recommended:

- Mandatory PKU testing,

- Behavior modification,

- More sheltered workshops and day programs,

- Additional federal funds for education in state-run institutions.

Mandatory PKU testing began in 1968 with 171,066 tests run over an 18-month period. Overall, 11 newborns were diagnosed with disabilities.

Minnesota developed an aggressive plan that took advantage of increased federal funding.

The first state program office was created in November 1971.

Headed by Ardo Wrobel, the office was responsible for designing, organizing, and executing state programs. Counties would continue to implement the programs locally and care for the people impacted by them.

Ardo Wrobel (center) headed the State's first program office for mental retardation.

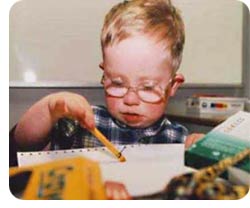

A break-through program called Project EDGE was introduced in 1969 at the University of Minnesota. The program was created to teach children aged three to five years of age with Down Syndrome.

Led by Professor John Rynders of the University of Minnesota, Project EDGE — which stood for Expanding Developmental Growth through Education — was federally funded.

Video: John Rynders, Professor, University of Minnesota, describes the innovative Project EDGE on Down Syndrome he directed.

Preschoolers with Down Syndrome benefited from Project EDGE, an innovative education program.