The 1970s: Developmental Disabilities. Millions Cured by Redefinition.

A Functional Definition. People First.

From a public policy and community service point of view, the 1970s saw a number of major changes in definition and perspective:

- The federal government recognized the broader concept of "developmental disabilities" which made funding available to people with a wider range of disabilities.

- The AAMR, then the federal government restricted the term "mental retardation" to exclude people with higher IQ scores. Among other consequences, this led to a very large number of children being excluded from special educational services.

- The federal government definition of developmental disability shifted from a categorical or labeling/diagnostic definition to a concern with the severity of functional limitations.

- The impact of the social and physical environments on the dignity and quality of life of individuals came to be more deeply understood and laid the foundation for understanding the extent to which the social and physical environment holds people back.

- The clarion call of people with disabilities themselves – "We are People First"

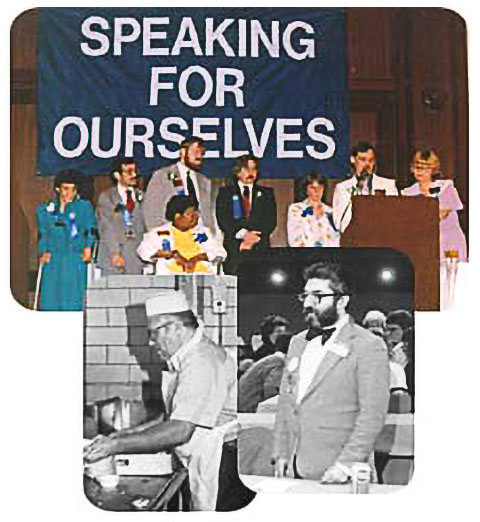

People First - Speaking for Ourselves

"Developmental Disabilities" Includes More People

Key legislation in the 1960s authorized federal support for mental retardation services. In 1970, the Developmental Disabilities Services and Facilities Construction Amendments significantly expanded the scope of federal legislation beyond mental retardation. The 1970 Act defined the term developmental disability:

"…a disability attributable to mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or another neurological condition found by the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare to be closely relate to mental retardation or to require treatment similar to that required for mentally retarded individuals…"

This definition was expanded in 1975 to include autism and dyslexia (so long as those with dyslexia also had another developmental disability). As before, the disability also had to be substantial in nature, have originated before the age of 18, and have continued or be expected to continue indefinitely.

The federal definition was intended to apply for planning purposes only. It was not intended to define eligibility for services. Over the years, however, state legislatures began to define eligibility for their services in terms of the federal definition. For instance, it was not until 1985 that the Minnesota Legislature recognized people "with other related conditions" and made them eligible for services.

DD Act – Protection and Advocacy

A More Restrictive Definition of "Mental Retardation" Excludes More People

In 1973, the American Association on Mental Deficiency changed its definition of mental retardation as:

Mental retardation refers to significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning existing concurrently with deficits in adaptive behavior, and manifested during the development period." (Grossman, 1977)

The AAMD also decided that the cut off for being labeled "mentally retarded" would be 70 on the IQ test.

As Burton Blatt commented, millions of people were "cured" with this redefinition. Generally, this meant that only 2.25% of the population would be labeled instead of 16%.

Burton Blatt

New Definitions and the Effects of Labeling

The main reasons for dropping the borderline category were its racial implications (racial minority groups were over-represented in the borderline group) and a growing uneasiness about the effects of labeling. It also meant that fewer students were eligible for special education services.

The new definition also extended the upper age limit of the developmental period to 18 years of age. That change was then reflected in the 1975 amendments to federal legislation.

This focus on adaptive behavior led to the development of scores of adaptive behavior scales that could measure the extent to which individuals' adaptive behaviors were deficient. These scales had their origins in the work of Goddard and Doll at The Vineland Training School in New Jersey. Goddard published his questionable work on The Kallikak Family.

Doll developed the concept of adaptive behavior and the Vineland Social Maturity Scale in 1935. The scale was adopted by the U.S. military in 1941. It became the basis for the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale still in use today.

Vineland Social Maturity Scale

Implications of a Funcional Definition

In the mid-1970s Lou Brown and his colleagues expanded our understanding of the implications of a functional definition. Brown challenged educators to reject the developmental model and instead use the criterion of ultimate functioning in the community to select skills based on current and future environments.

The term functional was the underpinning for a new curriculum model that promoted community access by targeting skills needed to function in daily life. By the late 1980s, strong consensus had emerged among professionals that curriculum should focus on age-appropriate functional skills.

Lou Brown

A Deepening Understanding of Normalization

In the 1970s Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger was working with the National Institute on Mental Retardation in Canada. His writing and training material greatly expanded our understanding of the consequences of stigmatization and service practices that treat people with more or less dignity.

It had many impacts, but one was to focus attention on the systematic ways that societal and human service practices harder for them to develop their gifts and talents. Societal and human services practices can forge definitions of people as deviant, devalued, and discarded, or as people who are valued citizens.

The people who developed such concepts as person centered planning and self-determination were early participants in normalization training. Normalization, then Social Role Valorization, training continued in the 1980s through the Syracuse University Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership and Change Agentry.

A number of concepts that gained greater currency were present either in Wolfensberger's or Nirje's description of the Normalization Principle in the late sixties and early seventies:

- Applying normative conditions to deviant people

- Striving towards the societal norm

- The notion that a single principle could apply to all deviant people, not just retarded or disabled people

- Historic deviancy roles

- Role circularities

- The developmental model

- (Deviancy) image juxtaposition

- Age appropriateness

- Life function separation (later, Model Coherency)

- Dispersal of services to avoid negative group dynamics among larger groups of deviant people and overloading social assimilation potentials

- Avoidance of deviant-person and deviant-group juxtapositions

- The distinction between physical and social integration.

Wolf Wolfensberger

Label Jars Not People

In the early 1970s, people with developmental disabilities gathered in conferences, first in British Columbia (Canada), then in Oregon. Out of the Oregon gathering came the name for a remarkable social movement – People First. (See the Self Advocacy section of Parallels in Time).

People with developmental disabilities called on the world to "Label Jars Not People". They proclaimed, "We are People First".

The persistent message of People First began a simple and straightforward understanding that people with developmental disabilities are people, not labels or clients. This means that their needs and rights are fundamentally the same as everybody else's.

The definition of people with developmental disabilities as "people" shifts the emphasis to the rights of all citizens being applied to all people, and the needs of all people being understood as the needs of people with developmental disabilities.

Over time this perspective radically changed the nature of individual planning. We came to understand that by focusing on an individual's humanness, supports take on a different tone than if the focus is on an individual's deficits.

People need love and relationships, power and rights, respect, meaning in life, money, experience and opportunities. "People" have choices about where and with whom they live. "Clients" or "the disabled" have choices made for them. Professionals assign them housemates and addresses.