The 2000s: Olmstead and the Struggle Over Rights and Resources

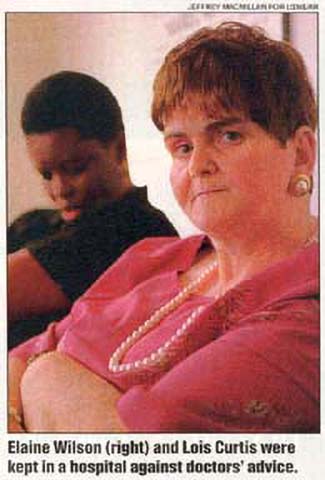

The right of people with developmental disabilities to live in the community was reinforced by the July 13, 1999 decision of the United States Supreme Court in Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W. Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson wanted to receive services from the state of Georgia in the community instead of in a psychiatric institution.

They argued that Georgia violated their right to services in the most integrated setting under the ADA. Their case went all the way to the Supreme Court.

The decision still leaves room for states to maintain "a range of facilities."

The court recognized that the ADA does not necessarily require a State to serve everyone in the community but that decisions regarding services and where they are to be provided must be made based on whether community placement is appropriate for a particular individual, in addition to whether such placement would fundamentally alter the State's programs and services.

Photo courtesy Jeffrey Macmillan

for US News &World Report

In the wake of the Olmstead decision, the federal government has issued a series of directives and suggestions for states to comply with the ADA.

Federal grants have been made available to expand community-based services. Dozens of states organized task forces to develop implementation plans.

Advocates filed more lawsuits against states consistent with the Olmstead decision.

The Department of Health and Human Services principles for state compliance with the ADA included:

- Develop and implement a comprehensive, effectively working plan

- Provide an opportunity for the public, including people with disabilities to be integral participants in the plan

- Take steps to prevent or correct unjustified institutionalization

- Ensure the availability of community-integrated services

- Afford people with disabilities the opportunity to make informed choices

- Take steps to ensure quality assurance in the delivery of community-based services

Photo courtesy Tom Olin

The United States Department of Health and Human Services also changed Medicaid rules so that Medicaid coverage was available to more low income people with disabilities and families with children with disabilities while living at home.

This helped reduce the bias that let people in institutions qualify for Medicaid at higher income levels than people in the community.

The Systems Change Grants for Community Living contained three grant programs to assist states to develop and implement their Olmstead plans.

The Nurses Facility Transition program provided grants to state agencies and community organizations to make community living arrangements available for people in institutions or at risk of nursing home placement.

In 2001, the federal government embarked on the New Freedom Initiative, a multi-agency effort to "remove barriers to community living for people of all ages with disabilities and long-term illnesses. It represents an important step in working to ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to learn and develop skills, engage in productive work, choose where to live and participate in community life."

Photo courtesy Tom Olin

By 2005, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services was describing the following types of accomplishments:

- $158 million from 2001-2003 in Real Choice Systems Change grants to 49 states, D.C. and two territories to help states develop programs.

- These grants included the "Money Follows the Person" demonstration projects in 8 states. The intent of these grants was to help states "re-balance their long-term support systems (institutional and community-based options) and permitting funding to follow the individual to the most appropriate and preferred setting."

- The Independence Plus Initiative to make it easier for States to request waives or demonstrations that offer families or individuals greater opportunities to take charge of their own health and direct their own services.

- Transitions from Institutions – the use of HCBS waivers to cover one-time expenses in the transition from institutions to "their own home in the community."

- Promising Practices repository of activities related to NFI initiatives.

Photo courtesy Mouth Magazine

Community Living – Your Life, Your Way:

A compilation of stories of individuals with developmental disabilities who are living in the community, where and with whom they choose to live.

Photo courtesy Tom Olin

All of these advances and plans were deemed at risk by 2003. State plans were systematically identifying long-standing barriers to complying with the Olmstead ruling. The state identified needs include:

- affordable and accessible housing

- transportation

- assessment tools to identify people's needs

- information tools to link people with services

- data systems of monitor quality and track people at risk

- adequate staffing

- education and outreach

- availability of funded Medicaid waivers

Shortfalls in state budgets and the resulting fiscal crises meant a higher need to contain Medicaid costs, not to expand them.

A National Health Policy Forum paper in 2003 concluded that "in light of such difficult barriers and a tight fiscal environment, implementation of Olmstead might be expected to grind to a halt in virtually all states."

Photo courtesy Charyl Walsh-Bellville

Tom Nerney: New Assumptions

One of the reasons for ongoing court cases, increasingly mounted by people with disabilities themselves, is to ensure that implementation does not grind to a halt. The challenge continues.

In 1972, a federal court ruled that the failure of the District of Columbia school board to provide a publicly-supported education to all children with disabilities cannot be excused by the claim that there are insufficient funds (Mills v Board of Education).

The challenge in the first decade of the new century focused on determining the extent to which rights trump resources.

Photo courtesy

Charyl Walsh-Bellville