Public Hostage: Public Ransom – Inside Institutional America

Chapter Fourteen: The Radiator

Seeing takes time. We live in a fast society—30 miles per hour, at least. What we see is so often like a billboard: colors, shapes, a quick message among an avalanche of quick messages—numbing. It doesn't take long to withdraw from all that, for most of us. There is only so much one can sort out, understand, emotionally recognize, respond to, use.

For a health worker, seeing—really seeing—is critical. Each time an opportunity arises to see, every sense must be alert. Every bit of experience and stored knowledge must be somewhere close at hand. Each time that one only half-sees, is blind to what one sees, misinterprets, makes false assumptions, has incorrect expectations, a life is at stake.

I don't want to romanticize the doctor or add to the mystique and awe in which medicine is held in the minds of people. Seeing is not any more than a good parent or a loving and dedicated worker does all the time, naturally.

But this is a problem for the professional who is trained to be detached and alienated from people— "Objectivity" is the cover term. It is a real chore for the professional to be natural, alert, and insightful. To feel identity with people rather than functioning in a role, in a status pose flowing from authority, from failsafe aspirations, possibly from even downright dislike of people and human service.

If the feeling of identification between server and served is underdeveloped or absent, seeing is arduous. Seeing, really seeing, requires feeling. It is the difference between human understanding and object spectating.

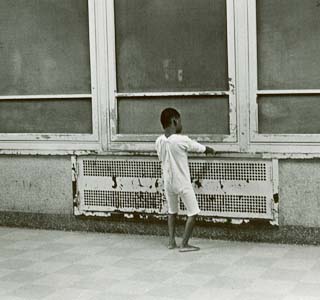

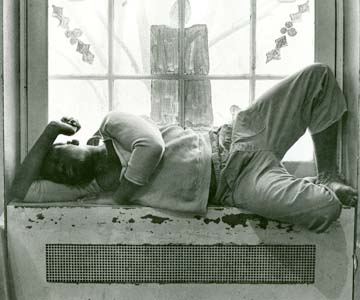

It is immensely hard to see in the institution. All of the deafening language of images built from the physical remoteness, steel doors, barren rooms, overcrowding, accepted suffering and degradation, make it almost impossible to see, to feel and identify with the victims as peers, citizens, friends, people. I guess it was the minute-to-minute struggle to "see" that made work so exhausting. I don't think that anyone can naturally identify with the people trapped in the institution without constant, conscious effort to redefine everything and to fight back the tendency to withdraw and close out what is really there to be seen and done. On all the wards there is nothing soft. The stone floors, wood and fiberglass chairs, Formica and chrome tables, steel and glass windows, iron beds. Hardness. Coldness. Hardness unyielding. No place soft. No place for warmth, solace, sanctuary, energy to support life; no place but one— the radiator.

There, for the lonely, the searcher, the instinctual migrant, a place four feet long and three feet high—an iron cover plate radiating something drastically different from all the rest. One has but to be passively close to feel warmth, a sensation, a tingle on the skin, on the nerve endings of one's being. It took me a long time to realize how important the radiator was to a community of people who had nothing. Once I saw the people huddling there, it still took time to really grasp, to feel the profound meaning of the radiator. At first I was outraged at the burns that I saw. People drugged, with a slowly diminishing ability to feel, sought the radiator for a retreat, a sleeping companion, a mother fragment; then, burned, were unable to move. Couldn't the workers watch out for people next to the hot plates? I didn't realize how powerful was the pull to crouch and curl up there, a pull like that which draws all life to the warmth and energy of the sun. The inn, which was here cut off. Here, there was only the paint-peeling, unmodulated sheet of hot metal left.

Can you imagine how empty, how deprived life can be, how empty of warmth? How can we not really see? How can we let the radiator be the sun for so many? There is always some sort of radiator, some obvious substitute for the real thing, around which the lives of the public hostages cling. We have to look with more than just our eyes.