1960s: Building the Momentum

A Declaration of Basic Rights

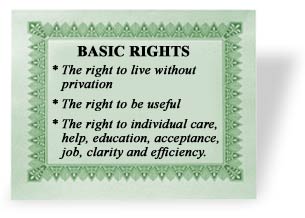

In June 1966, Governor Rolvaag issued a declaration of basic rights for people with developmental disabilities. These rights included:

- The right to live without privation,

- The right to be useful,

- The right to individual care, help, education, acceptance, job, clarity and efficiency.

By 1965, community care was in its infancy, serving 1,545 people. However, access to community care would soon explode.

While it cost less to serve people in private facilities, the state still paid only for services delivered through state hospitals.

Public pressure mounted to have the state pay for a portion of the expense of caring for people living in private facilities. The result was a reimbursement system that capped parent payments at $10 a month. The remainder of the cost was shared by counties and the state.

In 1966, Governor Rolvaag outlined rights for people with developmental disabilities.

Video: Milt Conrath acted as a witness during the Welsch trial regarding the conditions and practices of state hospitals.

Project TEACH

Using a Title 1 grant of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Cambridge hospital introduced Project TEACH in 1967.

It put into practice the theory that children can develop "life" skills and become self-sufficient if given appropriate individual attention.

During the 1960s, the number of residents in Day Activity Centers and Private Facilities grew at an increasing rate.

Before Project TEACH at Cambridge State Hospital

Film footage and script compliments of Roger Anderson, employee at Cambridge State Hospital (Run time 2:47)

After Project TEACH at Cambridge State Hospital

Film footage and script compliments of Roger Anderson, employee at Cambridge State Hospital (Run time 2:11)

Work Programs

Economics Laboratory, now known as Ecolab, was one of the first to hire people with developmental disabilities under an experimental work program designed to teach them viable skills.

When Frank Cerny, an Ecolab vice president, spoke to program graduates in 1967, he said, "Each of us has a special talent. We must discover our strong point, get training and find our place in the world."

American Express, Lutheran Brotherhood, Radisson Hotels and McDonalds followed suit by increasing their commitments to help find employment for people with developmental disabilities.

Economics Laboratory was one of the first companies to hire people with developmental disabilities.

Day Programs

By now, day programs had become a major focus for comprehensive services in all counties throughout the state. In March of 1967, the state Arc organization issued a positive report outlining the remarkable progress made by individuals with developmental disabilities participating in day programs.

This progress cost the state just 60 cents per hour for each participant, considerably less than traditional residential care.

In 1967, the U.S. Public Health Service awarded Hennepin County a $150,000 grant to fund day programs for three years. Meanwhile, mental health centers in Minnesota were given added duties, including responsibility for planning day programs for local citizens with developmental disabilities.

The Arc Report illustrated how day programs have helped people with developmental disabilities make significant progress at a low cost.

New Positions Approved

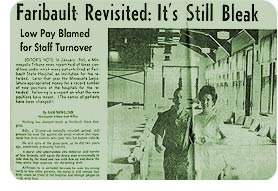

Despite this progress, the State Legislature approved nearly 2,000 new positions for state hospitals in 1966. Again, the media played a role in initiating change.

Sam Newlund, whose 1965 exposé in the Minneapolis Tribune uncovered serious deficiencies in the state hospital system, re-visited the topic in 1967. The follow-up series reported that, even with the new staffing levels, staff turnover rates at Faribault was 100 percent. Aides could not live on the low pay and many had to work double shifts.

Overall, turnover in the state hospital system was 35.7%.

Newlund, from the Minneapolis Tribune, did have some positive progress to report. By 1967, half of the men living in institutions wore shoes, largely because of staff efforts.

A 1967 expose revisited an earlier series only to find that little had changed.

Positive progress:

Half of male residents wore shoes by 1967.