With an Eye to the Past

1940s to 50s: Lighting the Fire

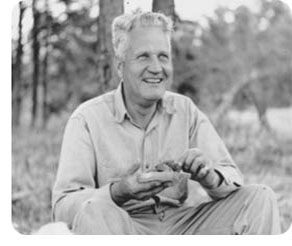

The quest for change began in earnest in 1946 when parent activists found a ready ally in Governor Luther Youngdahl.

Just beginning his first of three terms in office, Youngdahl was one of the first public officials to commit himself to improving the deplorable conditions that these "invisible" Minnesotans lived in at some state institutions.

View an index of documents (PDF format) related to developmental disabilities policy in the State of Minnesota from 1880s to the present time »

Governor Luther Youngdahl: Champion of Change

Deplorable conditions in the state's mental institutions

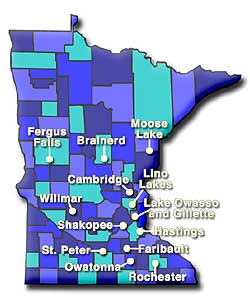

In 1948, an extensive newspaper exposé in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune detailed the living conditions in seven Minnesota state mental institutions – Fergus Falls, Moose Lake, Willmar, Anoka, Hastings, St. Peter and Rochester – and brought the issue to public attention.

Geri Hoffner, more well-known as Geri Joseph, published a 10-part report on the deplorable conditions in the state's mental institutions.

Remarkably, the report, which was critical of the current system, was created with Governor Youngdahl's full support and approval.

The findings described in Hoffner's series included: Extreme overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, inedible food, over-reliance on restraints, and severe understaffing.

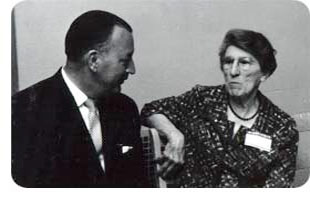

Geri Joseph

Video:

Geri Joseph, reporter for the Minneapolis Morning Tribune, did a series of articles on the institutions in 1948 and 1950.

Geri Hoffner's exposé created a public outcry.

Hoffner noted that in some institutions, so many residents were forced to sleep in a single bed that the only way to get out was to climb over the footboard.

The public's conscience was electrified when Hoffner compared residents' living conditions with those of the pigs in the neighboring pig sty.

Citizens were outraged when Hoffner pointed out that while the pig sty was heated and air conditioned and the pigs were bathed frequently, residents of the institution next door were not.

The superintendent of one state institution was quoted as saying, "The custody we give isn't as good as a state prison."

About two months earlier, members of the Unitarian Conference Committee presented similar, disturbing findings to Youngdahl.

Quarters were so overcrowded that residents had to crawl over the footboards to get in and out of bed.

Commitee Findings

During December 1947, its members had visited every state hospital and found that:

- The institutions suffered from decades of neglect;

- Restraints were preferred over treatment;

- Residents were not clothed or bathed;

- The food was not fit to eat;

- Overcrowding was so severe that there weren't even enough chairs.

In 1950, within two years of the exposé and the UCC report's findings, Youngdahl appointed Dr. Ralph Rossen as the state's first commissioner of mental health and hospitals. A visionary, Rossen brought a new philosophy to the care system. The focus, he said, must be on the individual rather than "mass care."

With residents outnumbering staff 100 to 1, personal attention was impossible.

State Support Must Start with the Individual

According to Rossen, every person is an individual with unique needs and experiences. Thus, state support must start with the individual. State hospitals were too often concerned with per capita costs and custodial care of large numbers of people, neglecting individual needs.

The only way to change, he said, was through persistent, consistent teaching and training of staff members.

As one of his first initiatives, Dr. Rossen set a goal that each resident should receive five minutes of individual attention during an eight-hour shift.

While that may sound ridiculously low by today's standards, it was considered unattainable at the time. With a ratio of one staff member for every 75 to 100 residents, residents were lucky if they received basic care.

In the 1950s, parents of children with developmental disabilities, especially those in Minneapolis and St. Paul, were becoming activists. In those days, children with disabilities were regarded with disdain, fear, or, even worse, seen as non-existent.

Dr. Ralph Rossen

Minnesota state-run institutions in the 1950s. Over the years, people with developmental disabilities were served by state-run institutions in 12 communities throughout Minnesota.

The most prominent organization at the time was the Minneapolis Association of Retarded Children, known as The Arc. Formed in December of 1946 by Evelyn Carlson and Reuben Lindh, its mission was to tackle issues related to treating children with developmental disabilities.

The Lindhs found common courtesy an effective way to bridge the gap. For years, the couple hosted appreciation teas for hundreds of state hospital employees to thank them for guiding, teaching and caring for the children entrusted to them.

Staff appreciation teas were an effective way to build bridges between caregivers and families.

An Invaluable Ally

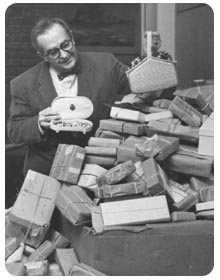

Cedric Adams, Minnesota's legendary newspaper columnist and well-known radio personality, proved an invaluable ally to those trying to improve the system.

In the early 1950s, the Department of Public Welfare enlisted his help to raise funds to purchase basic equipment and improve living conditions in the hospitals.

As director of guardianship for the state, Mildred Thomson recognized the formidable power parents had as advocates. Working closely with local groups, she played a key role in improving conditions and care for people with developmental disabilities from 1924 to 1959.

In addition to spending 35 years as Minnesota's director of guardianship, she was president of the nation's largest professional organization on mental deficiency and helped develop a national association for parents of children with developmental disabilities.

Cedric Adams: An invaluable ally

Photo permission granted by the Star Tribune/Minneapolis-St. Paul (2009)

Mildred Thomson: Bringing Parents Together