Drug Ads

Brain troubles? Sea sickness? Mania? Here's the cure for you!

Patricia Deegan photographed all the ads shown here from museum displays and from 20th century psychiatry trade journals. Comments are from Lucy Gwin of Mouth Magazine.

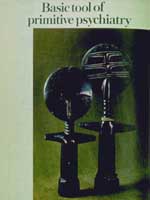

Advertisements of treatments for people with disabilities can tell us a lot about how society manages them in different eras. This ad is from the late 19th century.

The ad shows us that silly old auntie is terrified of cows! Can't have that. If nerve pills don't work, we'll have to send auntie to the asylum for expert management.

"Psychiatry," the ad tells us, "has advanced far beyond such crude devices for treatment of the mentally ill." We no longer spin out the devil; we drug it out.

Nearly every century since Hippocrates has brought so-called "great new advances" in treatment of people with disabilities, all of them abandoned when the next "great new advance" comes along.

Here the advance is insulin-induced coma, also known as "insulin shock treatment."

This display from the Glore Museum of Psychiatry explains the theory and practice of insulin coma.

Coma has several advantages for the management of people who are being treated against their will: it keeps them quiet for a while, and it often wipes out their memories for days, perhaps for their entire earlier lives outside the asylum.

This is a drug company advertisement for insulin shock treatment in trade journals for psychiatrists. The treatment was used only in institutional settings. Note that the ad advises "the closest possible medical supervision." When whole wards were treated at once, as was usually the practice, the treatment was sometimes fatal for a few of those treated.

As this ad demonstrates, nearly every new advance is quickly followed by a new treatment for its side effects.

The next great advance in the 20th century was electric shock treatment. When applied, it produces muscle convulsions so strong they break bones. Succinylcholine, shown here, paralyzes and thus relaxes muscles for Electro Convulsive Treatment (ECT). It is also a potent poison, the one chosen by Texas nurse Genene Jones when she took the lives of more than 47 infants, and by other medical professionals who became serial killers.

This ad is for another treatment for the side effects of ECT: an oxygen tool kit for management of what it calls "acute respiratory embarrassment" — euphemism for "an embarrassing death."

This powerful tranquilizer was advertised in the 1960s as facilitating "ward adjustment" — another euphemism, which means, "getting people to shut up and behave when locked away against their will."

The drug Thorazine was sold to doctors as an improvement over electroshock.

And now that chains are out of fashion…

… we have chemical restraint.

Now we can herd nearly all of our patients into one big day room! There. All better.

Once the "palsy" side effects of Thorazine, known by doctors as tardive dyskinesia became obvious, psychiatry introduced a new drug to make them less so.

By this time, it was taking two drugs to ward off side effects of the first. Be sure to specify the liquid — so you can sneak all three into their food.

Cogentin and other drugs for "palsy" were and are prescribed to mask the side effects — shaking and becoming confused — of many mind drugs.And hey, "mind drugs" is Ralph Nader's term for them, not mine.

When Thorazine's popularity waned on the wards, its maker laid claim to a huge new market, advertising it to pediatricians as a cure for…

… kids who won't behave the way we want them to.

Chloral hydrate, the most powerful sleeping medicine, here makes its debut as "daytime sedation" for troublesome patients in any congregate setting. It is widely used even now as "daytime sedation" in state "schools" and nursing homes.

Methedrine, now known as "meth," America's most dangerous drug…

… was once seen very differently. With the debut of this ad from the late 1950s, we begin to see the debut of outpatient drugging. Although ethical pharmaceutical companies were not in those days allowed to advertise to the general public, the word about new drugs soon got out.

Methedrine is no longer prescribed. But the genie is out of the bottle.

Back when it was popular to be neurotic and to be seeing a shrink — the early Woody Allen years — Miltown was all the rage, just as Prozac is today, when it's popular to call yourself depressed.

Here are two other early outpatient drugs, one an antidepressant, the other an early tranquilizer. Seeing that they both had unpleasant side effects, the next thing on the market was bound to be a combination of the two…

…Dexamyl. Shown at bottom "from the physician's viewpoint," it was prescribed primarily to keep middle-aged women from bothering their doctors.

Looky here! Some neurotic woman worrying about crowds and cancer. Today the doc is likely to prescribe Paxil and recommend a mammogram and a colonoscopy. But in the post-Freudian years, women were viewed as psychiatric hypochondriacs. What woman wouldn't be thrilled to stay at home all day and look after the house?

For decades, Equanyl was the most widely used "calmative" drug in nursing homes. Today it has an FDA black box warning against use by older people. Apparently its effects include causing confusion and, in some cases, death.

Here's Luminal, also known as phenobarbital. It's no longer used much for the "control of emotional turbulence" in institutional settings. Instead, you'll see it sprayed on crime scenes where, under blue light, it betrays blood stains.

Serial-killer doctors often use Seconal, which is still prescribed in institutional settings. State executioners, also physicians, employ it as the first of two drugs administered in death by lethal injection.

We hope you've had enough mind drugs here to last you a lifetime.

Here is one of the first consumer ads for a mind drug, Effexor. It promises that "You can achieve true wellness" — but not without a drug.