This opinion will be unpublished and

may not be cited except as provided by

Minn. Stat. § 480A.08, subd. 3 (2004).

STATE OF MINNESOTA

IN COURT OF APPEALS

A04-1812

Richard H. Hagstrom, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

City of Shoreview,

Respondent.

Filed July 5, 2005

Affirmed in part, reversed in part, and remanded

Peterson, Judge

Ramsey County District Court

File No. C2-01-005646

Rolf E. Gilbertson, Michael R. Cashman, Zelle, Hofmann, Voelbel, Mason & Gette, LLP, 500 Washington Avenue South, Suite 4000, Minneapolis, MN 55415 (for appellants)

Pierre N. Regnier, Jessica E. Schwie, Jardine, Logan and O’Brien, PLLP, 8519 Eagle Point Boulevard, Suite 100, Lake Elmo, MN 55042 (for respondent)

Considered and decided by Lansing, Presiding Judge, Peterson, Judge, and Crippen, Judge.*

U N P U B L I S H E D O P I N I O N

PETERSON, Judge

On appeal from summary judgment in this zoning-ordinance dispute, appellants argue that (1) the district court resolved factual issues against appellants and violated their due-process rights by appointing a referee and adopting his report over appellants’ objections; (2) appellants were denied equal protection by the city treating appellants’ property differently than the property of appellants’ neighbor; (3) the city’s conduct denied appellants substantive due process of law because appellants had a property interest in the city correctly applying its fence ordinance and the city did not do so; (4) the district court erred in ruling that ordinance section 205.080(F)(1) applies, and even if that section applies, the district court incorrectly interpreted it; and (5) appellants were entitled to a declaratory judgment identifying how the ordinance’s term “front yard” would be applied here. We affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand.

FACTS

Since

1989, appellants Richard and Deirdre

Hagstrom have owned the property located at

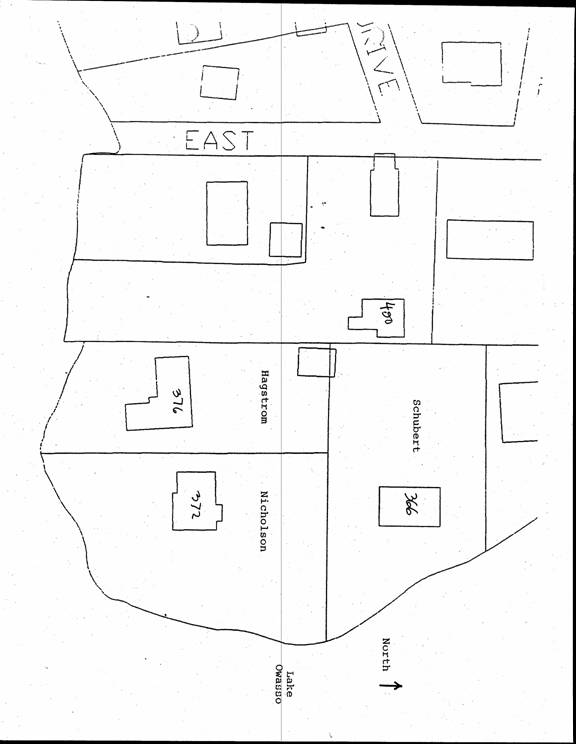

Following is a diagram of the properties:

In

1993, the respondent City of

In

July 1993, Richard Hagstrom met with the city building inspector to determine

the maximum size of the fence that could be built along the mutual boundary

line. The building inspector advised

Hagstrom that the fence could not extend southerly toward

In June 2000, the city issued Nicholson a permit to build a fence, 100 feet long by six feet high, along the mutual boundary line. The Hagstroms complained to the city that the fence encroached on their property; obstructed their view of the lake; exceeded the height permitted by the city’s development code; and did not meet the ordinary-high-watermark (OHW) setback requirement. The city’s building official inspected the fence and found that it encroached on the Hagstroms’ property, so the fence was moved onto Nicholson’s property. The city planner rejected Richard Hagstrom’s claim that the height and length of the Nicholson fence were contrary to the development ordinance. The Hagstroms appealed the permit decision to the Shoreview Planning Commission, which upheld the decision. The Hagstroms appealed the planning commission’s decision to the Shoreview City Council, which denied the appeal and upheld the decision issuing the building permit.

The Hagstroms brought this action in district court against the city alleging that a city ordinance was unconstitutional and that the city had improperly construed and applied its ordinances with respect to the fence construction permit issued to Nicholson in 2000; a permit issued to Nicholson in 1993 to build an addition to her dwelling; and the placement of Nicholson’s driveway. The Hagstroms also alleged that their constitutional due-process and equal-protection rights were violated because conditions that were imposed on them when they built a fence in 1993 were not imposed on Nicholson. The Hagstroms sought declaratory and injunctive relief, monetary damages, and attorney fees.

The city moved for summary judgment seeking dismissal of the complaint. The Hagstroms moved for partial summary judgment on all claims and reserving only the issue of damages. By order filed January 4, 2003, the district court denied both parties’ motions for summary judgment as premature. The district court concluded that Minn. Stat. § 555.11 (2002) required both that Nicholson, as an interested person, be made a party to the declaratory action and that the Minnesota Attorney General be notified of the claim that a city ordinance was unconstitutional. The court ordered that the lawsuit would continue when Nicholson was joined to the lawsuit and directed Hagstroms to verify compliance with Minn. Stat. § 555.11.

Following a scheduling conference, the district court appointed a referee to review and make a recommendation to the district court on the application of the ordinances at issue. The district court received the referee’s report on July 11, 2003, and by order filed July 16, 2003, the district court allowed the parties 30 days to file objections to the report and also stayed the requirement that Nicholson be made a party. The Hagstroms filed objections to the referee’s report, arguing that the referee misapplied the law and improperly made factual findings.

The parties again filed cross-motions for summary judgment, with the city seeking dismissal of all claims and the Hagstroms seeking summary judgment on all claims and reserving the issue of damages for trial. By order filed June 17, 2004, the district court denied the Hagstroms’ partial-summary-judgment motion and granted partial summary judgment for the city. The district court denied the Hagstroms’ motion for reconsideration but issued an amended order on July 13, 2004.

The July 13, 2004 amended order denied the Hagstroms’ partial-summary-judgment motion and granted partial summary judgment for the city on all claims except the claim relating to the placement of Nicholson’s driveway. The district court adopted the referee’s[1] report as part of the court’s findings and conclusions. The district court found no just reason for delay and expressly directed the entry of judgment. Judgment was entered on July 28, 2004.

This appeal challenges the partial summary judgment in favor of the city. The city filed a notice of review seeking review of the denial of summary judgment on the claim regarding Nicholson’s driveway.

D E C I S I O N

On

appeal from summary judgment, this court determines whether any genuine issues

of material fact exist and whether the district court erred in applying the

law. Cummings v. Koehnen, 568

N.W.2d 418, 420 (

I.

The Hagstroms argue that the district court improperly resolved factual issues against them. When deciding a summary-judgment motion, the district court may not weigh the evidence, but must resolve all factual inferences in favor of the party against whom summary judgment is granted. Wagner v. Schwegmann’s So. Town Liquor, Inc., 485 N.W.2d 730, 733 (Minn. App. 1992), review denied (Minn. July 16, 1992).

Citing the district court’s use of the terms “alleged” and “claimed,” the Hagstroms argue that the district court rejected the evidence that the city limited the height of their fence to four feet and did not allow the fence to extend toward the lake past the Hagstrom setback. We interpret the district court’s use of the terms “alleged” and “claimed” as a recognition that a factual dispute exists on that issue rather than as a factual finding contrary to the evidence presented by the Hagstroms. Also, the district court’s order incorporates the referee’s report, which states:

There is dispute about whether the City limited the height and location of the Hagstrom fence or merely documented in the permit what the applicant requested. However, noting a “4′ Max. Height” on the permit implies that the City was restricting the fence height.

The district court did not improperly resolve fact issues against the Hagstroms.

The Hagstroms also object to the appointment of the

referee, but they have not shown that they were prejudiced by the

appointment. To obtain reversal, an

appellant must show both error and prejudice.

Midway Ctr. Assocs. v. Midway Ctr.,

Inc., 306

II.

The city argues that this action should be dismissed because Nicholson was not joined as an indispensable party. In its January 4, 2003 order the district court directed the Hagstroms to join Nicholson as an indispensable party. But in its July 16, 2003 order, the district court ordered, “[u]ntil further order of the court, the court’s prior requirement that [] Nicholson be made a party to this lawsuit is withdrawn.” The stay of the order requiring Nicholson to be joined as an indispensable party remains in effect. Therefore, a decision by this court on the issue would be premature.

III.

The

interpretation of an ordinance is a question of law subject to de novo

review. Gadey v. City of Minneapolis,

517 N.W.2d 344, 347 (Minn. App. 1994), review denied (Minn. Aug. 24,

1994). Three general rules of

construction guide a court’s interpretation: terms in zoning ordinances are

given their plain and ordinary meaning; “zoning ordinances should be construed

strictly against [a] city and in favor of [a] landowner;” and zoning ordinances

must be considered in light of their underlying policy goals. Frank’s Nursery Sales, Inc. v. City of

Roseville, 295 N.W.2d 604, 608-09 (

The

district court determined that the city’s interpretation of the ordinance was

proper under the circumstances. The city

determined that the setback of Nicholson’s fence from

The city code contains

a general provision that requires that structures must be set back 50 feet from

the OHW of Lake Owasso.

In applying this

exception to determine the setback from

Consistent with

the general rule of construction that terms in zoning ordinances are given

their plain and ordinary meaning, the Shoreview City Code provides that

“[u]nless specifically defined [in the code], words or phrases used in the City

of Shoreview Code of Ordinances shall be interpreted to give them the same

meaning as they have in common usage and so as to give subject code its most reasonable

application.”

The city’s interpretation of section 205.080(F)(1) is consistent with the first common meaning of adjacent; the Schubert home is close to and lies near the Nicholson fence. But this meaning of adjacent cannot reasonably be used when interpreting the ordinance because there could be several existing structures that are close to or lie near the site of a new structure, and the city interprets the ordinance to identify two principal structures, not several structures. Therefore, the second common meaning of “adjacent” must be used, and this meaning does not allow the city’s interpretation because the ordinance refers to adjacent structures, not adjacent parcels. The Nicholson home stands between the Nicholson fence and the Schubert home and, therefore, the Nicholson fence is next to the Nicholson home; it is not next to the Schubert home. The existing structures that are next to, or adjacent to, the Nicholson fence are the Hagstrom home and the Nicholson home, not the Hagstrom home and the Schubert home.

The city’s

construction of the ordinance also leads to an absurd and unreasonable result

because the setback for a fence along the boundary between two parcels can be

significantly different depending on the side of the boundary where the fence

is located. See Minn. Stat. § 645.17 (2004) (stating that in ascertaining

legislative intent, courts presume that “legislature does not intend a result

that is absurd, impossible of execution, or unreasonable”). In this case, the home on the west side of

the Hagstrom home is set back much further from

We also note that the

exception from the general 50-foot setback requirement that is set forth in

section 205.080(F)(1) is not the only exception set forth in the

Setback requirements set forth in this section from side property lines and OHW level shall not apply to docks, piers, boat lifts, retaining walls, walks, required safety railings along steps and retaining walls, or vegetation (trees, shrubs, flowers, etc). Fences may be permitted anywhere lakeward of the required structure setback, except within the shore impact zone, provided they are not taller than 3.5 feet above grade. The City Planner may authorize fences up to 6 feet in height that exten[d] into the Shore Impact Zone when a property abuts a walkway, park, or similar facility.

The emphasized language in section 205.080(F)(2) appears to address the precise circumstances of this case and makes it unnecessary to determine whether Nicholson’s lakeside yard is a front yard. It is not apparent why the city did not apply this provision when issuing the permit for the Nicholson fence.

Because the city incorrectly interpreted section 205.080(F)(1) when it determined the setback for the Nicholson fence, we reverse the district court’s determination that the fence is a legal fence and remand to the district court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. On remand, the district court may reopen the record and may remand to the city to permit it to consider the applicability of section 205.080(F)(2) for determining the setback and the height of the Nicholson fence.

IV.

The Hagstroms argue that the city violated their equal-protection rights.

A zoning ordinance must operate uniformly on those similarly situated. . . . [T]he equal protection clauses of the Minnesota Constitution and of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution require that one applicant not be preferred over another for reasons unexpressed or unrelated to the health, welfare, or safety of the community or any other particular and permissible standards or conditions imposed by the relevant zoning ordinances.

The

Hagstroms argue that under Nw. College,

the city is required to apply the same conditions to the Nicholson fence that

were applied to the Hagstrom fence.

The disparate treatment of Northwestern and Bethel is constitutionally impermissible. Because Bethel has long been allowed to pursue its course of construction merely by complying with Arden Hills’ requirements in obtaining building permits, no more may be required of Northwestern on the instant application.

Today’s decision is limited to ordering that Arden Hills grant a building permit to Northwestern to construct its proposed fine arts center, subject only to an application for such permit in the usual form and substance therefor. Arden Hills is not otherwise bound in perpetuity by what it has asserted to be prior erroneous applications of its zoning ordinance and may in the future require Northwestern to exhaust its administrative remedies by application for the appropriate rezoning of its campus.

Unlike

the parties in

V.

The Hagstroms argue that the city violated their due-process rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

In order to establish a section 1983 claim, [plaintiffs] must establish that they have been deprived of a right, privilege, or immunity secured by the constitution or law of this state by any person acting under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, or any State or Territory. A substantive due process claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in the zoning context exists, if at all, only in the extraordinary situations and will not be found in “run-of-the-mill” zoning disputes. To establish such a claim, the court considers (1) whether there has been a deprivation of a protectible property interest, and (2) whether the deprivation results from an abuse of governmental power sufficient to state a constitutional violation.

State law and the city’s ordinance recognize that certain adjacent property owners can sue to require enforcement of the zoning laws. It does not necessarily follow, however, that this right confers a protectible property interest for purposes of the substantive due process clause and 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Minnesota law has recognized that zoning ordinances do not create a property right in adjacent landowners: Setback lines or building lines do not really create an easement in the strict legal sense. The effect of setback lines and open yards and spaces in zoning ordinances is merely to regulate the use of property. It gives no beneficial use to another, except as light and air may rest undisturbed in the space where structure are prohibited. This restriction of use is based upon the exercise of the police power for the general welfare, and is not based on contract rights or the exercise of the power of eminent domain. . . .

Even assuming for the sake of further analysis that [plaintiffs] could establish deprivation of a property right, in the zoning context, whether government action is arbitrary or capricious within the meaning of the Constitution turns on whether it is so egregious and irrational that the action exceeds standards of inadvertence and mere errors of law.

Mohler

v. City of St. Louis Park, 643 N.W.2d 623, 635-36 (Minn. App. 2002)

(citations and quotations omitted), review

denied (

Here,

the record shows that confusion exists as to how to apply the conditions of the

Shoreview City Code to lakeshore lots.

The city’s conduct does not rise to the level of egregious conduct

required to support a section 1983 claim.

See id. at 636-37 (concluding

that the city’s negligent misrepresentation of the law did not rise to the

level of egregious and irrational conduct that would support a substantive due

process claim) (citing Northpointe Plaza

v. City of Rochester, 465 N.W.2d 686 (

VI

By notice of review, the city seeks review of the denial of its motion for summary judgment on the Hagstroms’ driveway claim, arguing that the Hagstroms’ claim was not ripe because they failed to exhaust their administrative remedies. In denying the motion, the district court retained jurisdiction “until the driveway issue is resolved, or until the administrative remedies . . . are exhausted.” On appeal the city argues that the district court erred in retaining jurisdiction over the claim and that the proper remedy was to dismiss the claim. We agree.

“Generally, a

party aggrieved by a decision of a municipality’s governing body must exhaust

all administrative remedies before seeking judicial review.” Med.

Servs., Inc. v. City of

The district court directed the parties to pursue their administrative remedies but retained jurisdiction. When administrative remedies exist, the proper procedure is for the district court to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claim without prejudice for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction so that plaintiffs may pursue administrative remedies.

Affirmed in part, reversed in part, and remanded.